A NASA spacecraft has slipped into Jupiter’s orbit for the start of a 20-month-long dance around the solar system’s largest planet to learn how and where it formed.

Success! Engine burn complete. #Juno is now orbiting #Jupiter, poised to unlock the planet’s secrets. https://t.co/YFsOJ9YYb5

— NASA (@NASA) July 5, 2016

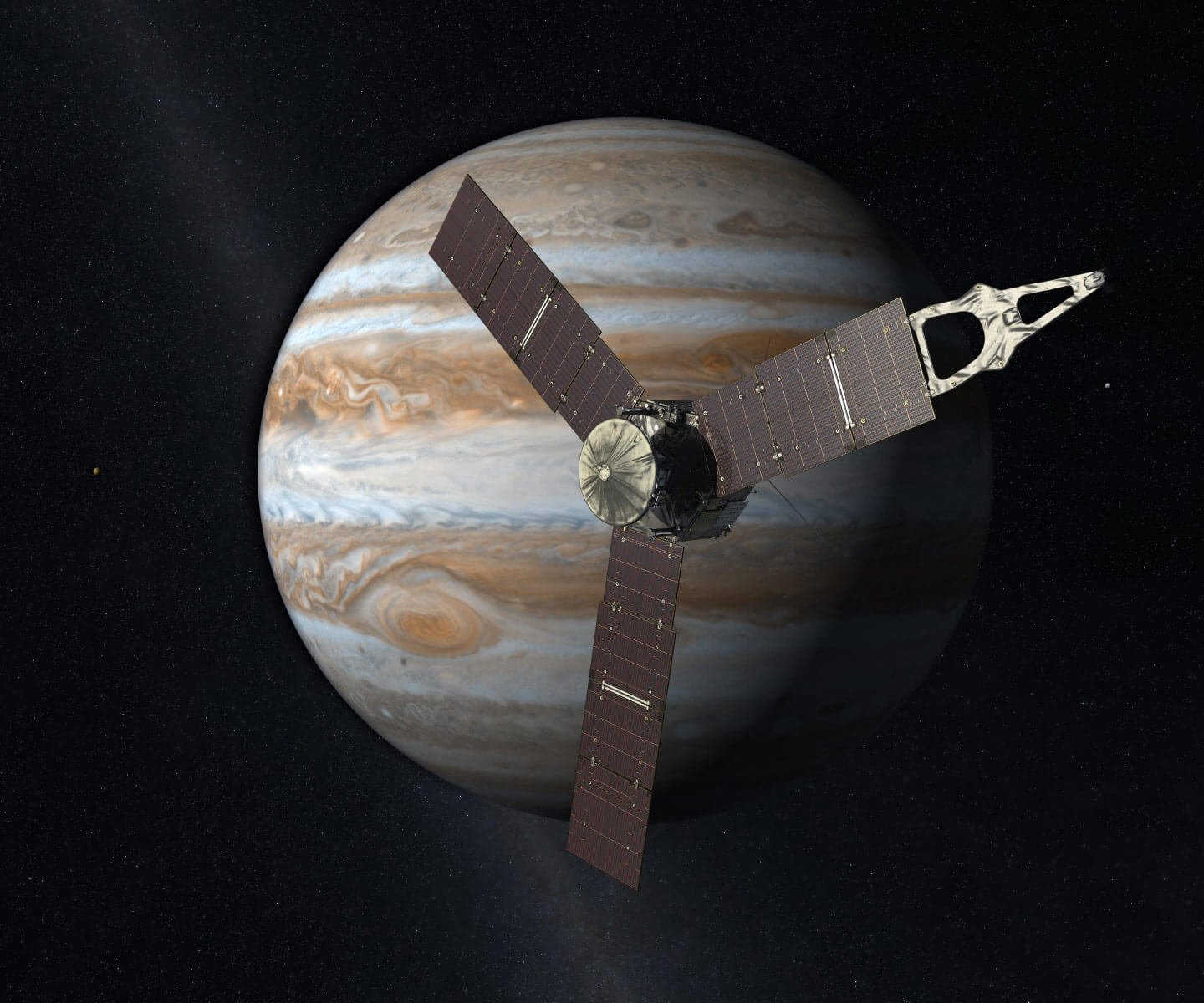

The Juno probe streaked closer toward Jupiter at 200 times the speed of sound in the empty vacuum of space.

“We’re barreling down,” Juno lead scientist Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio told reporters on Monday.

By noon on Monday, Juno had sailed past three of Jupiter’s four main moons, with volcanic Io, the innermost big moon, in its sights.

Launched from Florida nearly five years ago, Juno must be precisely positioned, ignite its main engine at exactly the right time and keep it burning for 35 minutes to shed enough speed so it can be captured by Jupiter’s gravity.

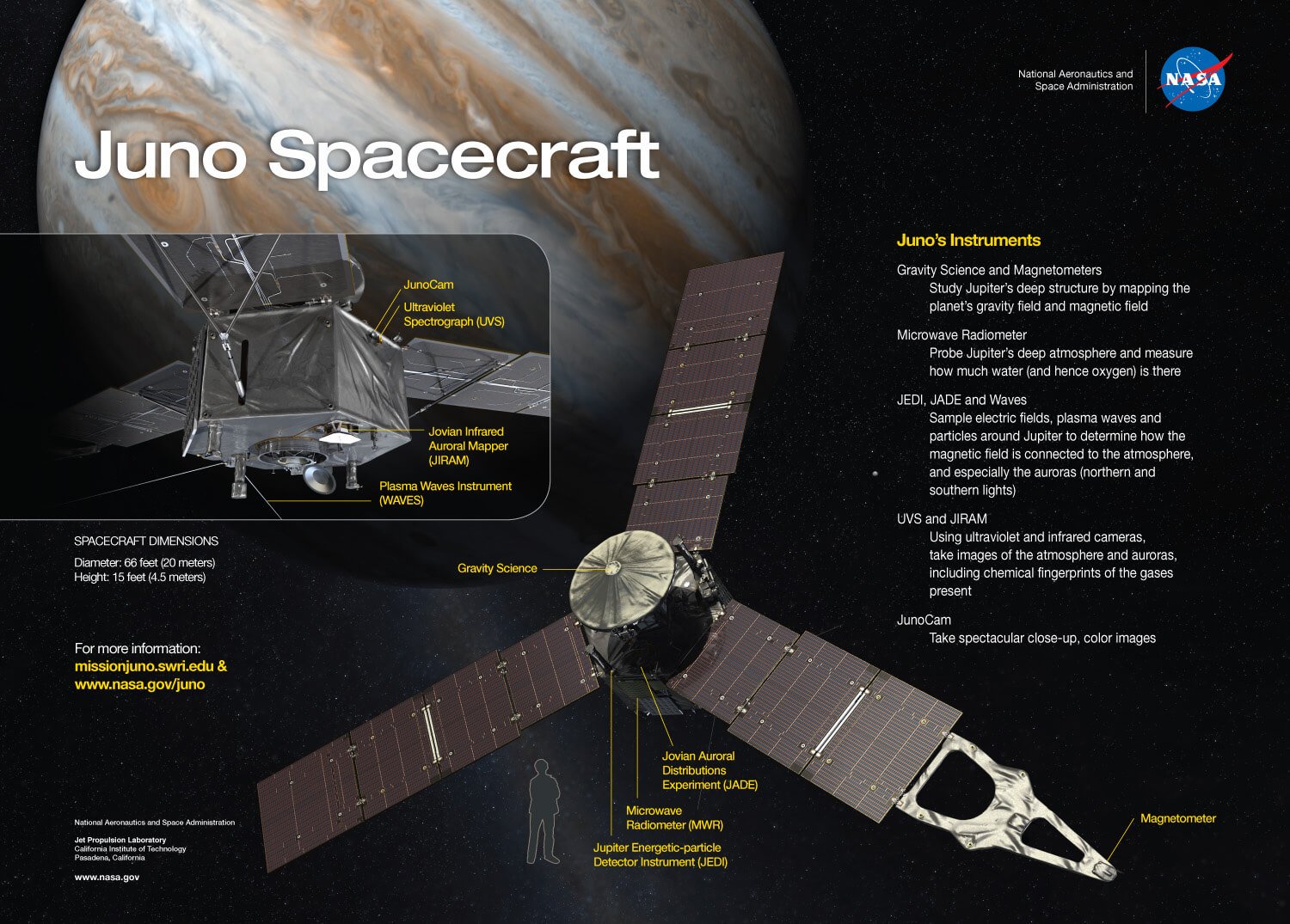

Scientists are particularly interested in learning how much water Jupiter contains, which is key to determining where in the solar system it formed. Jupiter’s origins, in turn, affected the development and position of the rest of the planets, including Earth and its fortuitous location conducive to the evolution of life.

The immense gravity exerted by Jupiter’s sheer size – packing 2-1/2 times the mass of all the other planets combined – is thought to have helped shield Earth from bombardment by comets and asteroids.

“We are learning about nature, how Jupiter formed and what that tells us about our history and where we came from,” Bolton said.

The Juno probe is named for the ancient Roman goddess, who was the wife and sister of Jupiter, the mythological king of gods, and had the power to see through clouds.

‘MUSICAL NOTES’

Only one other spacecraft, Galileo, has ever circled Jupiter, which is five times farther away from the sun than Earth and is itself orbited by 67 known moons. Bolton said Juno is likely to discover even more.

Seven other U.S. space probes have sailed past the gas giant on brief reconnaissance missions before heading elsewhere in the solar system.

Ground control teams monitored Juno’s progress during its do-or-die engine burn by listening for a series of radio signals.

“They really are musical notes. Based on what musical note is sent, we will know how something is doing,” Bolton said.

During its approach, Juno was lucky enough to fly through Jupiter’s tenuous rings without being hit by particles zipping around so fast that even a speck the size of a blood cell could prove fatal.

The risks to the spacecraft will not end now. The probe must quickly turn around and face the sun so its 18,698 solar cells can begin recharging the battery.

“I won’t exhale until we are back sun-pointing again,” Bolton said.

Juno will fly in highly elliptical, egg-shaped orbits that pass within 3,000 miles (4,800 km) of the tops of Jupiter’s clouds and inside the planet’s powerful radiation belts.

Engine burn complete and orbit obtained. I’m ready to unlock all your secrets, #Jupiter. Deal with it.

— NASA’s Juno Mission (@NASAJuno) July 5, 2016

Juno’s computers and sensitive science instruments are housed in a 400-pound (180-kg) titanium vault for protection. But during its 37 orbits around Jupiter, Juno will be exposed to the equivalent of 100 million dental X-rays, said Bill McAlpine, radiation control manager for the mission.

The spacecraft, built by Lockheed Martin, is expected to last for 20 months. On its final orbit, Juno will dive into Jupiter’s atmosphere, where it will be crushed and vaporized.

Like Galileo, which circled Jupiter for eight years before crashing into the planet in 2003, Juno’s demise is designed to prevent any hitchhiking microbes from Earth from inadvertently contaminating Jupiter’s ocean-bearing moon Europa, a target of future study for extraterrestrial life.