He called himself “The Greatest,” and few disagreed.

Muhammad Ali — who died on Friday in Arizona at age 74 — was one of the iconic sporting heroes of the 20th century, the three-time heavyweight champion of the world who said he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

Ali, who came of age amid the turmoil of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, dazzled the boxing world as a youngster with his speed, never before seen in his weight class.

He also rattled the established order with an equally quick wit and colorful personality that lifted him into the realm of super-stardom and ushered in the age of globally televised multi-million-dollar fights.

The legendary fighter spent his last years ravaged by Parkinson’s disease but never retreated from public view. Instead he added a crusade against the illness to the list of battles of his extraordinary life.

Rocky road to stardom

The rise of Ali — born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr in Louisville, Kentucky on January 17, 1942 — to the status of sports icon was not a smooth one.

His conversion to Islam in 1964, announced when he was fresh from victory over Sonny Liston for his first heavyweight world title, deeply disturbed white America.

His decision to change his name from what he called his “slave name” of Cassius Clay was derided.

But that was nothing compared to the outrage that greeted his refusal to join the armed forces in 1967 on the grounds that he was a Muslim minister.

Only 25 years old, he was convicted of draft dodging, stripped of his title and banished from boxing.

He was allowed to resume his career in 1970, but feelings were slow to heal. An unidentified man interviewed on camera in 1971 spoke for many when he called Ali’s impending title fight with Joe Frazier “a disgrace.”

“I have no interest in this fight at all,” the man said. “In fact, the reason is this fellow they call Clay, or Muhammad Ali, or whatever he wants to call himself, is a disgrace to the nation.”

Ali suffered his first professional defeat in that fight, on March 8, 1971 at Madison Square Garden.

On the same day, the US military was ordering investigations into charges that American soldiers had murdered Vietnamese civilians at My Lai.

A few months later, on June 28 of that year, the Supreme Court voted 8-0 to overturn Ali’s draft dodging conviction.

“They did what they thought was right, and I did what I thought was right,” Ali said of the government’s long struggle to imprison him.

That battle left its mark on Ali both inside and outside the ring.

In the 1960s, Ali relied on speed and reflexes, taking risks that other fighters would have paid dearly for.

After his enforced absence, he was a slower, craftier fighter, but one who still flouted the rule book and got away with it.

Epic fights

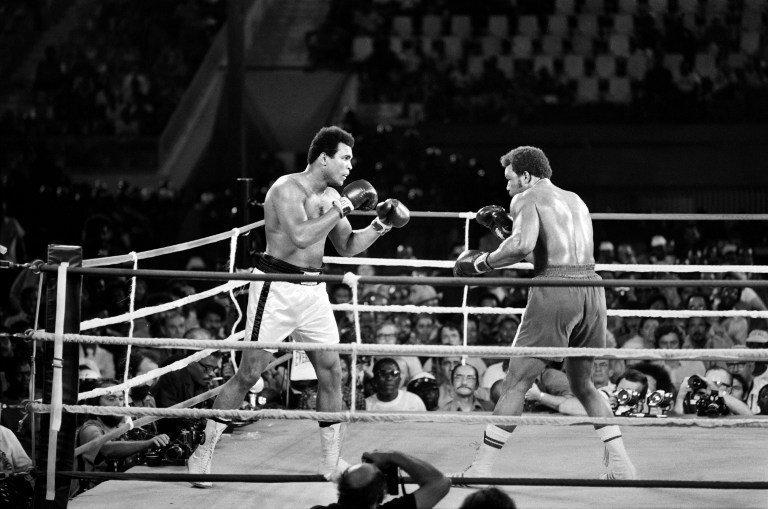

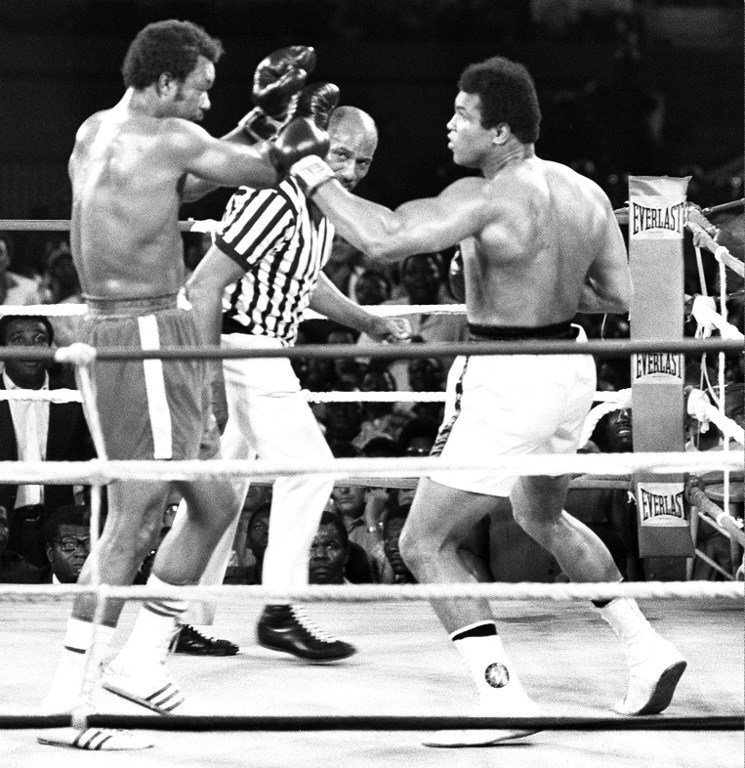

In 1974, Ali set his sights on a second world title, promising the greatest miracle “since the resurrection of Christ.”

In boxing terms, he delivered when he knocked out George Foreman in the eighth round in Kinshasa, Zaire — the famed “Rumble in the Jungle” — to regain the title taken from him in 1967.

Eleven months later, he triumphed in the “Thrilla in Manila” — an epic 14-round battle with Frazier that ended when Frazier failed to answer the bell for the 15th round.

Although the two were bitter rivals in the ring — and sometimes out of it — Ali was among the mourners at Frazier’s funeral in November 2011.

Ali’s courage and the strength of his chin kept him standing under brutal onslaughts that would have felled other fighters.

He once said he reckoned he had taken 29,000 punches, and his ability to withstand such punishment no doubt contributed to the Parkinson’s disease from which he suffered in later years.

“What I suffered physically was worth what I’ve accomplished in life,” he said in 1992. “A man who is not courageous enough to take risks will never accomplish anything in life.”

Ali lost the heavyweight title to unheralded Leon Spinks on February 15, 1978, but won it back in a rematch in September the same year, becoming the first three-time heavyweight world champion.

But the accomplishments he cherished later in life were outside the ring.

He used his popularity to spread the word of Islam, giving fans his autograph on religious pamphlets.

“Boxing made me famous,” he said. “This is the real thing. My main purpose in life is to be the world’s greatest ambassador, to spread the word of Islam.”

In doing so, Ali also opened a window on the world for black Americans, US civil rights campaigners said. “Ali helped to internationalize black consciousness as much as anybody,” said the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

“He has given people all over the world a sense of pride,” said Andrew Young, a civil rights activist and former US ambassador to the United Nations. “Oppressed people and people of color have been able to identify with him.”

Global icon

Ali’s stature as a global icon was confirmed with his poignant appearance at the opening ceremony of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, where he lit the cauldron.

Nine years later, in November 2005, then president George W. Bush awarded Ali the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

Even as his physical capacities diminished — his gait becoming more shambling and his speech more hesitant — Ali’s public life continued.

In 2002, he appeared with his wife, Lonnie, before Congress to press for more funding for Parkinson’s disease research.

Ali, who was named a UN messenger of peace in 1998, continued to involve himself in various charitable ventures, and he campaigned for boxing reform, calling for a national body to oversee the sport he loved.

In 2002, he visited Afghanistan to raise awareness of the problems still faced there after the fall of the Taliban regime.

By that time Ali was already familiar with the role of overseas envoy, having visited five African nations in 1980 on behalf of president Jimmy Carter.

In 1990, on the eve of the Gulf War, he travelled to Iraq and met Saddam Hussein in an independent effort to promote peace in the region.

He was credited with securing the release of 15 US hostages.

One of the hostages, Harry Brill-Edwards, told an Ali biographer: “I’ve always known that Muhammad Ali was a super sportsman. But during those hours that we were together, inside that enormous body, I saw an angel.”

(Feature image source: Reuters)