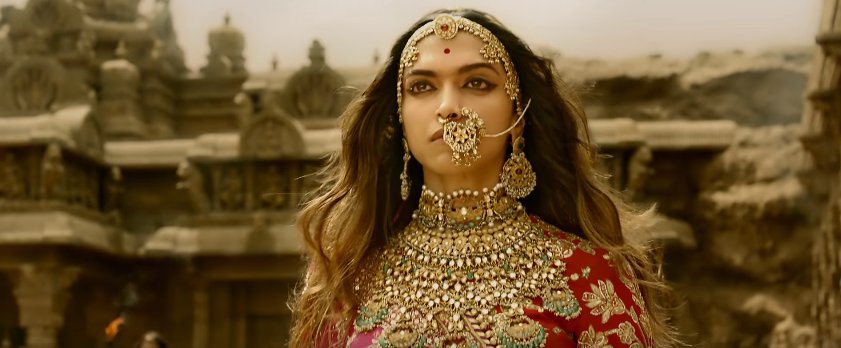

Threats have been issued. Swords have been drawn. One of India’s top actresses has been warned her nose will be sliced off. An office bearer of the country’s ruling party has supported beheading call of an actor and a film director. He even doubled the reward amount whosoever carries out the act – all for a movie, on a female folk character whose existence is as disputed as fact from fiction.

But that hardly seems to be of any value for the opponents of Sanjay Leela Bhansali-directed Padmavati. Such vociferous and brazen has been the opposition that a fringe group, proclaiming to represent Rajput “honour”, is dominating headlines of a nation of 1.25 billion people.

At least three states have publicly admitted to the pressures of the Shri Rajput Karni Sena stating that it might cause law and order problem in their states if the movie is screened without edits.

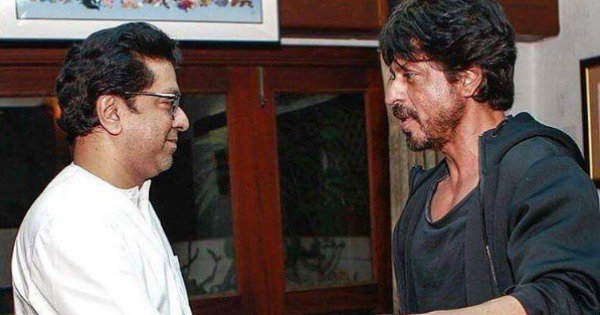

MNS-Model

Films running into rough weather with fringe elements is not new to India. Neither is the cowering down of political leaders and art industry before their threats. For decades now, Bollywood has been often kept hostage by fringe groups who are not very famous for respecting law and order.

Just last year, “pioneers” of Marathi nationalism, Maharashtra Navnirman Sena were so much riled up against Pakistani artists working in India, that they issued a 48 hours ultimatum to all the Pakistani artists to leave India. But that wasn’t it. The Sena also threatened the release of Karan Johar’s Ae Dil Hai Mukshkil (the movie had one Pakistani actor in the lead) until the producers didn’t pay Rs 5 crore to the Army relief fund. Army veterans had lashed out at MNS Chief Raj Thackeray for involving Army into politics and “extorting” money in its name.

What was more shocking was that when the film finally got a go ahead for release, the deal between the producers and MNS was brokered by Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis.

Something similar seems to be on the cards of Padmavati row as well. Chief Ministers of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have expressed a somewhat tacit approval of the tactics voiced by Karni Sena. That a serving Chief Minister personally wrote to Union information and broadcasting minister Smriti Irani to ensure that ‘Padmavati’ is not released without necessary changes to the film, is an acknowledgement of the clout the fringe group holds within the establishment.

While there hasn’t been any specified demand from the Rajput group yet, it’s worthy to mention that Sena’s ride on Rajput pride has also paralleled with its long-term demand of reservation for Rajputs in the state of Rajasthan. The amount of mileage Padmavati row has given to the outfit is phenomenal when compared to its organizational base.

There’s also an “extortion” angle to the Karni Sena. An India Today sting operation in September revealed how members of the Sena were forthright in staging attacks on film sets and then offering “protection” to the producers from mobs.

It’s true Padmavati is not the first film to come in the line of fire of Rajput groups. However, Padmavati row has brought together a wider confluence of Rajput groups even from outside of Rajasthan. The agitated Rajputs have marched on Delhi’s streets without shying away from threatening violence if the film is not binned.

They have already threatened that tourists would not be allowed to enter the historic Chittorgarh Fort – one of the major sources of tourism revenue for the state.

Padmavati Politics

The founder of Karni Sena Lokendra Singh Kalvi is a seasoned politician. He has been with Congress, BJP, floated his own party and even contested elections. That’s why the prism of Rajput identity to look at the Padmavati row tells only half part of the story.

Like most of the north Indian states, Rajasthan is also a caste-divided state and groups are rarely known to change their political allegiances. While Jats, Muslims, scheduled castes (SC) and scheduled tribes (ST) have traditionally been Congress supporters, BJP enjoys a widespread support among upper-caste Rajputs. It’s for this reason, the ruling BJP government has failed or chosen not to pacify opponents of Padmavati. Not surprisingly, Congress, eyeing future, has largely remained silent too.

The Rajput opposition also feeds into the larger Hindutva political project. Essentially, the row over Padmavati movie is that a Hindu queen was courted by a 14th century Muslim ruler sultan Alauddin Khilji. That she chose to self-immolate than fall to the overtures of Khilji has developed into a cultural folklore of Rajputs, spanning centuries. The controversy serves as a readymade recipe for consolidation of the Hindu vote bank by polarizing the debate into “native” ‘Padmavati’ and “outsider” Khilji.

Rather than putting the Padmavati debate to rest – by academic engagement and artistic expression – it seems the controversy is not being milked by Rajputs alone.