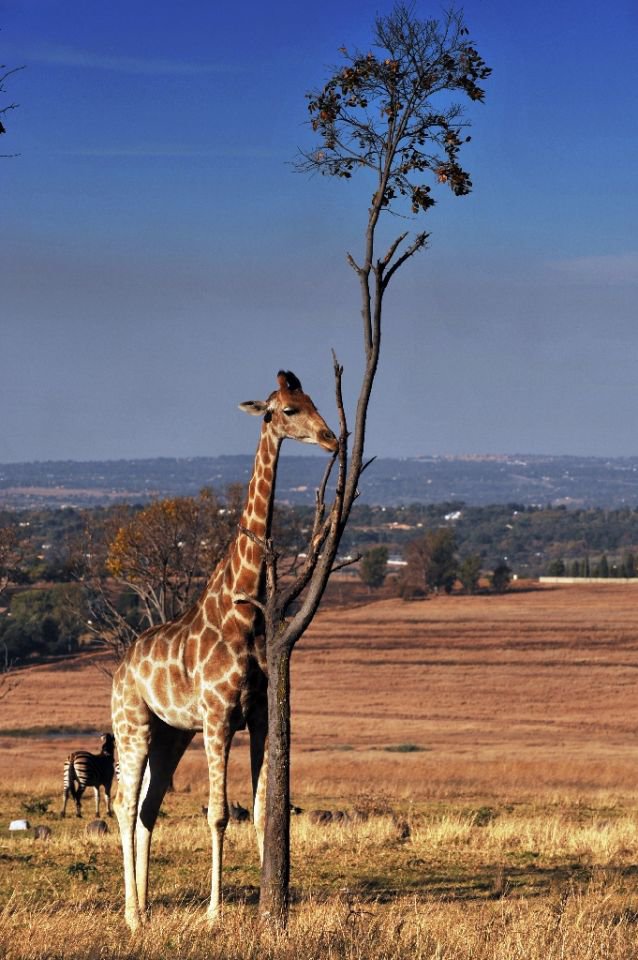

Wild giraffe numbers have plummeted by 40 percent in the last three decades, and the species is now “vulnerable” to extinction, a top conservation body warned on Thursday.

The population of the world’s tallest land mammal dropped to below 100,000 in 2015, mainly due to shrinking habitat and illegal hunting, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reported.

The group added 742 newly-discovered birds to the global species inventory, but said 11 percent were already facing annihilation and 13 previously unknown species have already disappeared in the wild.

“These majestic land animals are undergoing a silent extinction,” Julian Fennessy, co-chairman of the IUCN’s specialist group on giraffes, said in a statement.

Previously, giraffes held the status of “least concern” on the IUCN’s Red List, which tracks the conservation status of fauna and flora and ends with the category “extinct”.

Giraffes are spread out across southern and eastern Africa, with smaller pockets in west and central Africa.

Of nine distinct subspecies, four small populations saw increases. But four larger ones experienced sharp declines, and one remained stable, according to the report.

Numbers have crashed in 30 years from an estimated 157,000 to about 97,500 last year, the IUCN said.

The main culprit is the ever-expanding human population, which has caused a spike in poaching and encroachment upon the giraffe’s natural habitat.

“As one of the world’s most iconic animals, it is time that we stick our neck out for the giraffe before it is too late,” said Fennessy.

The report was part of an update of the Red List, unveiled at a meeting in Cancun, Mexico of the 196-nation Convention on Biological Diversity.

The global assessment now covers 85,604 species of plants and animals, of which 24,307 face the threat of extinction.

“Many species are slipping away before we can even describe them,” said IUCN director general Inger Andersen.

The update “shows that the scale of the global extinction crisis may be even greater than we thought,” she said.

Earth has entered a “mass extinction event” in which species are disappearing 1,000 to 10,000 times more quickly than just a century or two ago, according to scientists.

There have been six such wipeouts in the last half-billion years, some of them claiming up to 95 percent of all lifeforms.

The revised Red List now catalogues 11,121 species of birds.

The recently described Antioquia wren of Colombia is now listed as “endangered”, in part because half of its habitat risks being wiped out by a single dam, planned but not yet built.

Most of the newly discovered birds were known but are being recognised for the first time as distinct species.

Those already deemed extinct — preserved in lab and museum specimens — were island-dwellers, making them vulnerable to predatory or disease-carrying invasive species such as mosquitos that transmit avian malaria.

The Pagan reed-warbler from the South Pacific, along with the Oahu akepa and Laysan honeycreeper from Hawaii, are examples.

“Unfortunately, recognising more than 700 ‘new’ species does not mean that the world’s birds are faring better,” said Ian Burfield, science coordinator for BirdLife International, which collaborated in the global assessment.

“Unsustainable agriculture, logging, invasive species and other threats are still driving many species towards extinction.”

Illegal wildlife trade driven by collectors is emptying forests of some species, the reports said.

Such trafficking caused the African grey parrot of central Africa — prized for its ability to mimic human speech — to be reclassified from “vulnerable” to “endangered”.

A recent analysis in Nature of nearly 8,688 “threatened” or “near-threatened” animal and plant species showed that three-quarters are over-exploited for commerce, recreation or subsistence.

More than half are suffer the conversion of their natural habitats into industrial farms and plantations, mainly to raise livestock and grow commodity crops for fuel or food.

A fifth of species are affected by climate change.