The recent gas leak at the LG Polymers factory in Vizag, Andhra Pradesh that killed eleven people and affected over 2,000 residents of five villages in the vicinity has not only jeopardised the future of the people around the factory, has also led people to question the safety measures of others living around many more chemical factories in the country.

While chemical leaks aren’t something new for people in India, the problem is that it’s a recurring disaster. On the same day when the Vizag incident happened it turned out to be the day of industrial disasters with 8 workers sustaining burn injuries due to a boiler room blast at NLC India’s thermal power plant in Neyveli, Tamil Nadu while 7 workers, 3 of whom are in critical condition at a paper mill in Raigarh, Chhattisgarh fell ill after a gas leak at the plant.

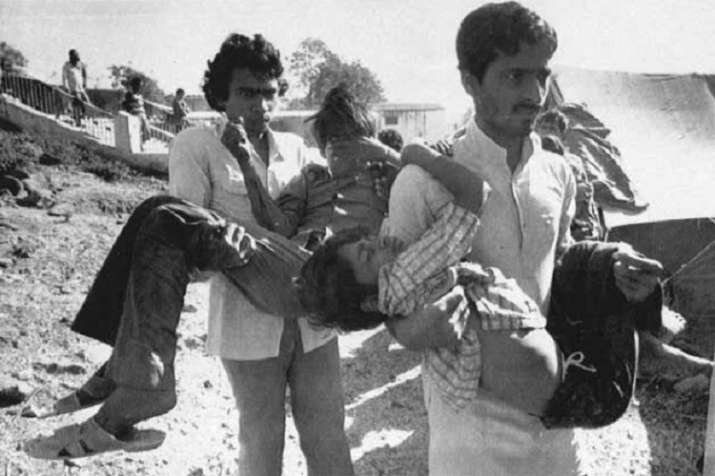

The 1984 Bhopal Gas Tragedy is considered to be the world’s worst industrial disaster with 3,500 killed and many others still facing the brunt of it. What followed, was the realization that if industrial development was unregulated and reckless without adequate safeguards the consequences could be far-reaching. Alongside, the demand grew for accountability of industries that engage in potentially hazardous activities.

At the time of the Bhopal gas tragedy, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) was the only relevant law specifying criminal liability for such incidents, soon after the tragedy, the government passed a series of laws regulating the environment and prescribing and specifying safeguards and penalties.

Some of these laws were:

– Bhopal Gas Leak (Processing of Claims) Act, 1985, gives powers to the central government to secure the claims arising out of or connected with the Bhopal gas tragedy. Under the provisions of this Act, such claims are dealt with speedily and equitably.

– The Environment Protection Act, 1986, gives powers to the central government to undertake measures for improving the environment and set standards and inspect industrial units.

– The Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991, an insurance meant to provide relief to persons affected by accidents that occur while handling hazardous substances.

– Chemical Accidents (Emergency Planning, Preparedness, and Response) Rules, 1996, this seem to have been framed for the exact purpose of monitoring plants or industries like the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal. It sets up a Central Crisis Committee with the secretary of the environment ministry as chairman and twenty other members “to deal with major chemical accidents and to provide expert guidance for handling major chemical accidents”. It has provisions for state-, district- and even local-level crisis groups.

– The National Environment Appellate Authority Act, 1997, under which the National Environment Appellate Authority can hear appeals regarding the restriction of areas in which any industries, operations or processes or class of industries, operations or processes shall not be carried out or shall be carried out subject to certain safeguards under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

– National Green Tribunal (NGT), 2010, which was set up by an Act of Parliament in 2010. The Act provides for the “principle of no fault liability”, which means that the company can be held liable even if it had done everything in its power to prevent the accident. The compensation that is ordered to be paid by the NGT is credited to the Environmental Relief Fund scheme, 2008, established under Public Liability Insurance Act of 1991.

– The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010, is the most recent law that has provision for compensation of more than ₹100 crore, which could reach up to ₹ 1,500 crore, depending on severity. It also comes with a cap of three million special drawing rights (SDR), an international reserve asset that countries can use to supplement their official reserves. The constitutional validity of this Act has been challenged in the Supreme Court and the case is pending.