Four years ago, India lost one of its finest litterateurs and veteran novelists, Mahasweta Devi, as she passed away in her Kolkata home at age 90. Apart from her contributions to literature, she was also an active social worker, and a staunch fighter for the rights of the oppressed and downtrodden. So what makes Mahasweta Devi such a treasured jewel in the nation’s cap?

Mahasweta Devi, the Writer

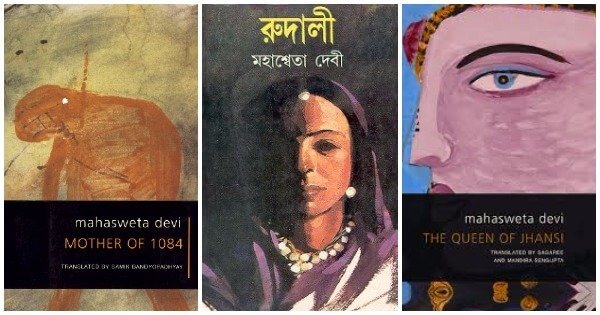

Though her works comprises of several novels, short stories and poems, she is perhaps best known for her novels Haajaar Chaurashir Ma, Tin Korir Shaad, Aranyer Adhikar, Rudali and Breast Stories, among others. Many of her works have also been adapted to films.

As a writer, she worked with themes that moved her. She was a traveller, and her stories and novels reflected a deep understanding of human nature, of class and its struggles, of social oppression based on caste and class, and human suffering and bondage. She drew her protagonists and literary characters from real people that she met during these travels, and her language was wonderfully normal. It was a bold statement against the high-brow, lyrical and often inaccessible prose adopted by other prominent authors at the time.

Apart from novels, Mahasweta Devi was also a spirited journalist and social worker, taking notes and understanding history as best as she could through sources that aren’t usually touted as ‘official’. Her first work, Jhaansi’r Rani (a biography), was more an alternate account of the Indian princess from alternate sources, and not official records. She was the first writer in India to attempt this format of retelling history: one collected not from official ledgers or documents but from word-of mouth stories and unofficial records recounted by locals, especially the downtrodden classes.

Mahasweta Devi, The Social Activist

Mahasweta Devi dedicated a large part of her career researching and writing about the ‘savage’ tribes of West Bengal (Lodhas, Shabars), of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and also about Dalits. A staunch opponent of the oppressive, colonial Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, which classifies around 150 Indian tribes as ‘born criminals’.

Among her recent activities, the most notable ones are her critique of the land grabbing from farmers in West Bengal for industrial purposes, and her role in co-founding Budhan Theatre, a theatre group consisting of members of the Charra tribe, one of the many tribes considered ‘criminal’ according to CTA.

Mahasweta Devi, The Feminist

Among her other works, Mahasweta Devi’s writings on women (Breast Stories, Old Women), reflect the status of women, historically and in current times, in Indian society. Known for her de-constructionist style, Devi quickly worked through the layers of patriarchy to uncover the vulnerable women of India as being engulfed in a vicious net of self abnegation and religious duty.

She focuses on women from subaltern classes as well as rural women, and brings out with lyrical clarity the enmeshed superstitions and dearth of education that trap these women in their roles. Of Women, Outcasts, Peasants and Rebels is one such seminal work in this regard.

Mahasweta Devi, the Awardee

The veteran writer has been bestowed with every single award that India could offer. She won the Sahitya Akademi Award for her novel Aranyer Adhikaar (Right To the Forest), then went on to win the prestigious Padma Shri. After that, she won the Jnanpith Award, one of the highest literary awards in India. She received the Padma Vibhushan, and the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and the Creative Communication Arts. She also holds an Honoris Causa From IGNOU and a Bangabidhushan, the highest civilian award in West Bengal.

Mahasweta Devi, A Force To Reckon With

Though born into a well-to-do Bengali family of academicians and artistes, (her father was a famous writer during the Kallol era in Bengal, her mother was a writer, her uncle was the eminent filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, her brothers were both eminent personalities), according to those close to the writer, the woman felt most at home with the poor, with whom she would spend days on end talking to and living with.

Her stories drew life force from human suffering, and were not afraid to use dark humour and irony to bring out the realities she was trying so hard to bring to the fore. To follow her passions, she walked out of her marriage to Bijon Bhattacharya, the star of the IPTA movement in Bengal, and as a consequence, was forever criticised. The separation also meant a severance of ties with her son, who she would continue to share a terse relationship with all her life.

Mahasweta Devi lived a full life. And everything she wrote about or talked about still continues to be relevant, today more than ever.

(All images sourced from Twitter)