The 16th World Sanskrit Conference was held in Bangkok on Sunday, 28th of June 2015. It was e xternal a ffair minister Sushma Swaraj’s first time at the event. Her messages in Sanskrit impressed many on Twitter but they did not convince scholar Ramesh Bhardwaj that the Narendra Modi Government was taking enough measures to revive research in Indian classical languages.

“There is no clear roadmap for Sanskrit research. The reason, I suspect, is that the government and its advisers are themselves not clear about what it means and what it takes to build both quality research and a pipeline of potential researchers,” Ramesh Bhardwaj, the head of Sanskrit department at Delhi University told The Telegraph .

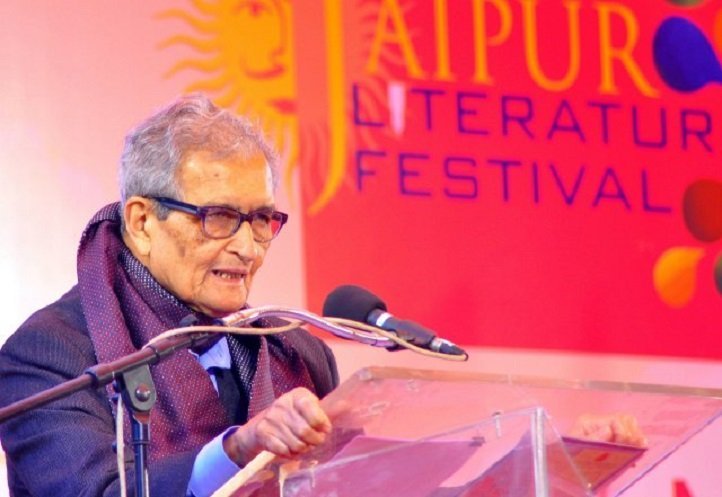

Scholars often fear that public diplomatic outreach may end up as little more than ‘tokenism’ amid a constant domestic indifference. Something that economist Amartya Sen had highlighted at the Jaipur Literature Festival in January 2014.

Sen had called classical languages the ’emotional content of a culture’ and asked India’s government to enhance investments into their research and humanities as opposed to a lopsided focus on the sciences.

Human resource development minister Smriti Irani, along with Modi, read out a carefully crafted message on bringing back Sanskrit to Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan schools in 2014 after it was displaced by German.

However, after a year it assumed office, there has been no other evidence that the Modi Government plans to uphold India’s classical languages, including the much gushed over Sanskrit.

Internationally, nations which are keen on preserving their classical languages have adopted a three-step process:

1. Introducing these languages in schools

2. Protecting traditional forms of learning (examples in the Indian context will be gurukuls and madarsas )

3. Contemporary research at universities.

It might also be beneficial for India if the government adopts this method.

The government had announced the celebration of a ‘Sanskrit Week’, soon after it came to power in 2014, in schools affiliated to CBSE board.

Scholars logically point out that India needs to learn a lot from some European countries which keep classical languages in schools as a mandatory subject. They do not just keep it mandatory in government-led schools neither do they keep it only as a subject of study for a week in a year. For example, Rome has kept Latin as a mandatory subject in Italian high schools. Italy has a system of schooling called the Liceo Classico where Latin and ancient Greek are compulsory subjects but India lacks any organised gurukul system for Sanskrit. The language is either optional or not taught in Indian schools at all.

“Tell students that they can choose one classical language, but then make sure they study that. This shouldn’t be looked at from the prism of religion — that Muslims should study Arabic or Persian, and Hindus Sanskrit,” said Masud Anvar Alavi, head of the Arabic department at Aligarh Muslim University, to The Telegraph .

The research scene in India is hypocritically bad. While the government is all set provide funds to Bangkok to run a cultural event with Sanskrit scholars, one of the country’s top Sanskrit research institution in Delhi is struggling to stay afloat. The Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan was allocated zero fresh funds in both the July 2014 budget and in the February 2015 budget. The institution had no vice-chancellor for over a year and a half before Parameshwara Narayan Shastry, a Sanskrit scholar, was appointed in April this year.

Relief arrived when Rohan Murty, son of Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy, contributed $5.2-million grant to Harvard University Press to publish works of Indian classical literature in both the original language and in English. Harvard University Press will publish fiction, non-fiction, poetry and religious texts in Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Sanskrit, Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, Persian, Arabic, Telugu, Urdu, Malayalam and Buddhist texts in Pali.

However some scholars do see a ray of hope in the government’s support for the Sanskrit conference and in the global renaissance in research on classical languages.

“I’m optimistic. You have never had an Indian foreign minister attending such a conference, even though it has been held for decades. And in this conference, we are treating Sanskrit like a living language. It’s very good if the government supports such initiatives. What you don’t want is the support reduced to tokenism. There’s a lot that needs to be done,” said Amarjiva Lochan, a Delhi University Sanskrit professor who is participating in the conference.