It may be inside a protest rally, or in front of a deadly shooting. Smartphones, video and social media are empowering citizens to tell their stories like never before.

This became clear with the live video earlier this month from Diamond Reynolds when she captured the aftermath of the shooting by a police officer of her boyfriend Philando Castile in Minnesota and streamed it live on Facebook.

The unprecedented live feed was just the latest in a series of events highlighting the power of citizen journalists to bring to light events and viewpoints that would otherwise not be part of mainstream media.

Citizen journalism has been around for centuries, but each technological advance has made it easier to reach more people, said Valerie Belair-Gagnon, who heads the Yale University Information Society Project and is an incoming professor of journalism at the University of Minnesota.

Prominent examples from the past include the 1963 Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination and the 1991 beating by Los Angeles police of Rodney King and the events of the Arab Spring.

More recently, citizen videos offered immediate and intimate perspectives from Thursday’s truck attack in the southern French city of Nice and the 2015 rampage in Paris, as well as dozens of citizen confrontations with police in the United States.

“In each case, a new technology prompted us to be aware that citizens can contribute journalism in certain ways,” Belair-Gagnon said.

“In the shift we are seeing since 2004, citizen media is becoming fully integrated to journalism.”

Belair-Gagnon said the rise of citizen journalism is not necessarily negative for the mainstream media.

“For me, it’s a positive story because journalists are not the only gatekeepers,” she told AFP.

“The fact that the public or citizens are able to gather information and distribute it to the public provides an opportunity for richer storytelling.”

Democratising media

Jeff Achen, executive editor of the Minnesota nonprofit group The UpTake, which trains citizen journalists, said the latest incidents show a “democratisation” of the news media.

“Media can’t be everywhere, but there is something with a citizen telling their own story from their own perspective which can be very valuable.”

Achen, a former television and print report, said citizen journalism won’t necessarily replace traditional media but may augment it.

“With the legacy media, some of the news can feel manufactured and manipulated. It can feel corporate sponsored,” he said.

Citizens can enhance journalism’s traditional role of holding powerful institutions like the police accountable.

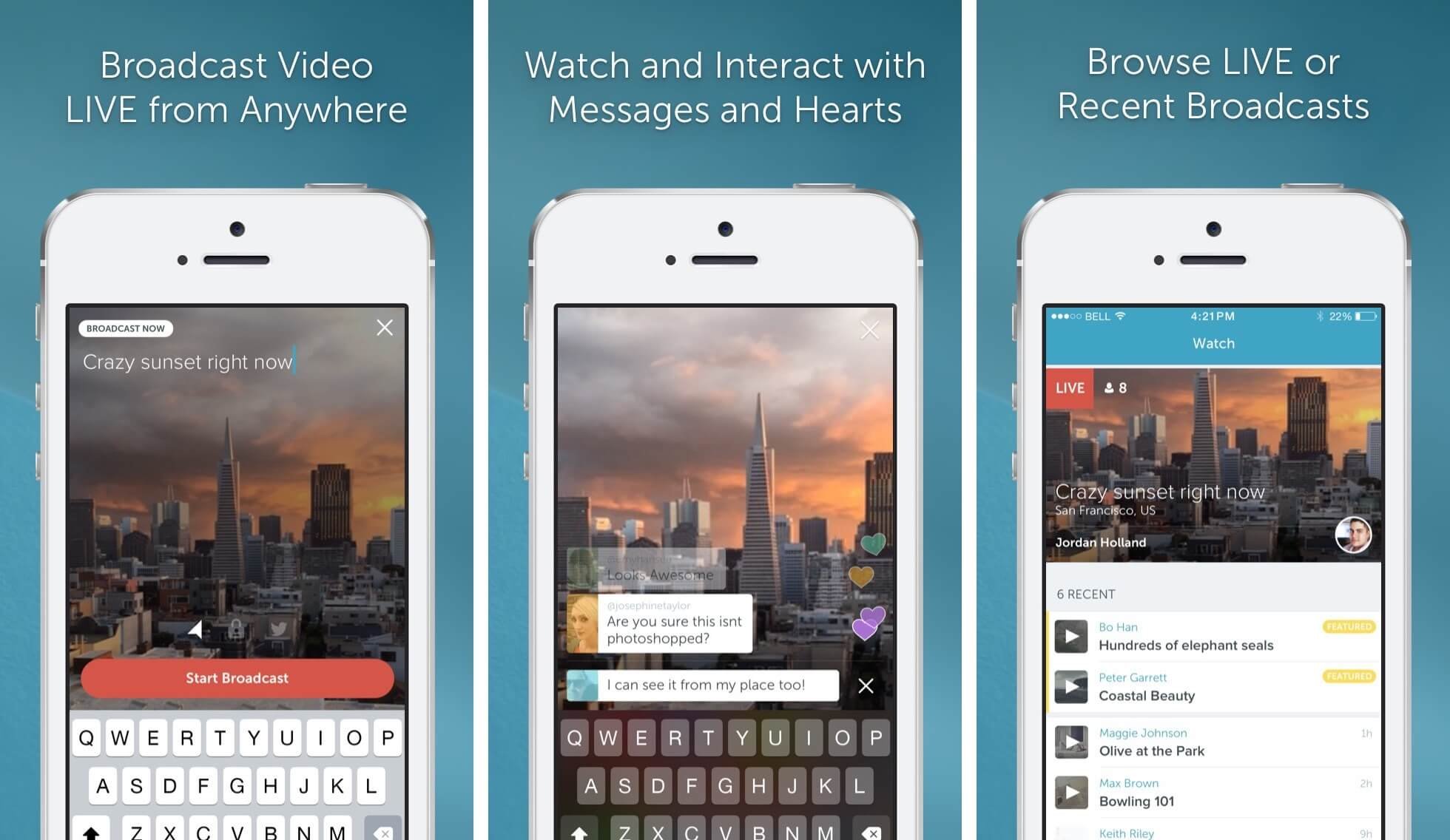

Platforms such as Twitter’s Periscope and Facebook Live, which allow anyone to broadcast an event, can create “excitement” in this effort, said Achen.

“I think this will become more prevalent,” he added.

“Everyone is going to make it routine. They will take out their cellphones whenever a police officer pulls over and does something” to bear witness to the facts, Achen said.

Ethan Zuckerman, director of the Center for Civic Media at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said the ability for citizens to reach the masses can help drive social change.

“Powerful as these videos are for mobilizing activists, they may be more powerful in bringing new participants into the racial justice movement,” he said in a blog post.

Change accelerating

Dan Gillmor, an Arizona State University professor and author of a book on citizen journalism, said Reynolds “changed our perception of media” with the “shocking and heartbreaking real-time web video of the last minutes of Philando Castile’s life.”

Gillmor said the Reynolds video was not necessarily something new but showed “the velocity of change is accelerating” in citizen news production. “Her video was a three-faceted act: witnessing, activism and journalism,” Gillmor said in a blog post.

“Even though few people saw it in real time, she was saving it to the data cloud in real time, creating and — one hopes — preserving a record of what may or may not be judged eventually to have been a crime by a police officer. What Reynolds did was brave, and important for all kinds of reasons.”

Gillmor said Reynolds “taught the rest of us something vital: We all have an obligation to witness and record some things even if we are not directly part of what’s happening.”

These events also raise questions about how platforms such as Facebook respond to their role as conduits for citizen journalism.

Facebook’s role came into question when it briefly took down Reynolds video, before restoring it.

Gillmor and others argue that the event underscores that Facebook is part of the news industry, despite its claim to be a neutral platform.

“Facebook hasn’t given a plausible explanation for its initial removal of Reynolds’ video,” Gillmor said.

“The point is that the video remains visible because Facebook allows it to be visible.”

Gillmor added that it is “enormously dangerous that an enormously powerful enterprise can decide what free speech will be. I don’t want a few people’s whims in Menlo Park overruling the First Amendment and other free speech ‘guarantees.'”