Seventy per cent of those who voluntarily opt for the Indian Special Forces fail.

Seventy per cent. Let that sink in.

The Indian Special Forces are the crème-de-la-crème of our soldiers, men who train in ‘expectation of the absolute worst’. There is no training manual. What they endure to pass a whole year of brutal training and probation must remain in the shadows. What we do know is that they have to go through an unforgiving regime of physical torture tests, coupled with terrifying trials that judge their mental toughness, while they are deprived of sleep and combating starvation. All this is designed to find their ‘breaking point’. If that breaking point is ever found, they’re out.

While I was researching Operation Jinnah, I heard several hair-raising tales from serving Special Forces officers. I narrate just a few here.

No Special Forces soldier forgets the ‘stress phase’ of training. One officer was ordered to begin his sleep deprivation cycles right at the start: the first cycle lasted three days without sleep; the second cycle, five days. He then had to stay awake in a standing position for a whole week.

Finally, at the end of that week, he was grilled for two hours about a war drill where an officer on probation had ‘fucked things up’ – all to see if the officer would break and give them the name just so they would let him rest.

Then there was the officer who remembered how his seniors randomly ordered high intensity physical tasks during a regular mental stress test, ‘just to mix things up’. He was ordered onto a treadmill at a very high speed and incline, in full combat gear, for 15 minutes, while three senior officers stood next to him and screamed out his flaws. It nearly broke him. Nearly.

During a field survival training at an uninhabited island in the Andaman & Nicobar, a squad of Marine Commandos had been deployed for eight days without rations – a simulated marooning in a warfare setting. The men had to prepare their own drinking water from the dew they collected and eat off the land – crabs, mostly. The island had no vegetation; they woke up at sunrise and conducted amphibious drills with weapons all day long, as the harsh tropical sun beat down on them. By the end, four of the men were at the end of their limits.

A para-commando is not just a warrior; they also have to train for two other key tasks: intelligence gathering and developing local contacts. In Jammu and Kashmir, two officers were asked to wear burqas and walk alongside a nullah down a hill to a village near the team base, and then cross back. It was a small settlement, but a hostile one, a stopping point for terrorists infiltrating via the Uri-Bandipora area. They very nearly failed. The task has never been ordered since.

Then there’s the story of the hangul.

It’s a tale I will never forget. Every time I think of it, I can smell it.

On a June afternoon, an unmarked Maruti Gypsy was making its way towards the Srinagar-Bandipora highway when the driver slams the brakes at something lying on the road. Two men step out of the vehicle to have a closer look, and they find the carcass of a large deer. A hangul perhaps, native to J&K, but they aren’t sure. Flies are swarming over the animal’s eyes, tongue and the pulpy wounds on the blood-stained fur.

Then one of them orders the other to ‘open it’. The junior doesn’t flinch. He pulls out a 9-inch hunting knife, gets on his knees and plunges the blade into the dead animal’s stomach. He tightens his grip, and in one motion, slices the animal open from its stomach to the base of its rib cage. He parts the animal’s rotting flesh. A horrible stench rises. The senior doesn’t blink. The junior runs the back of his hand unconsciously across his nose. He is then issued a second order: ‘Place your head in the carcass.

The junior pauses for a moment. He holds apart the flesh, holds his breath, and buries his head in the carcass. He tries not to breathe. The flies swarm to this new feast. Suddenly, the he feels the steel grip of the senior forcing his head deeper into the animal’s guts. He gasps, the festering fluids coating his face. His head is held inside the rotting deer for a whole minute, maybe longer.

The senior, a Major, and the junior, a Lieutenant, belonged to a Special Forces team from a battalion of the Army’s Parachute Regiment. The Lieutenant was in his second week of probation, a three-month period that soldiers spend in their active units before they are declared fit and worthy of operations.

‘We train in expectation of the absolute worst,’ he told me. Having his head shoved into a dead deer was a mere appetizer for what would follow.

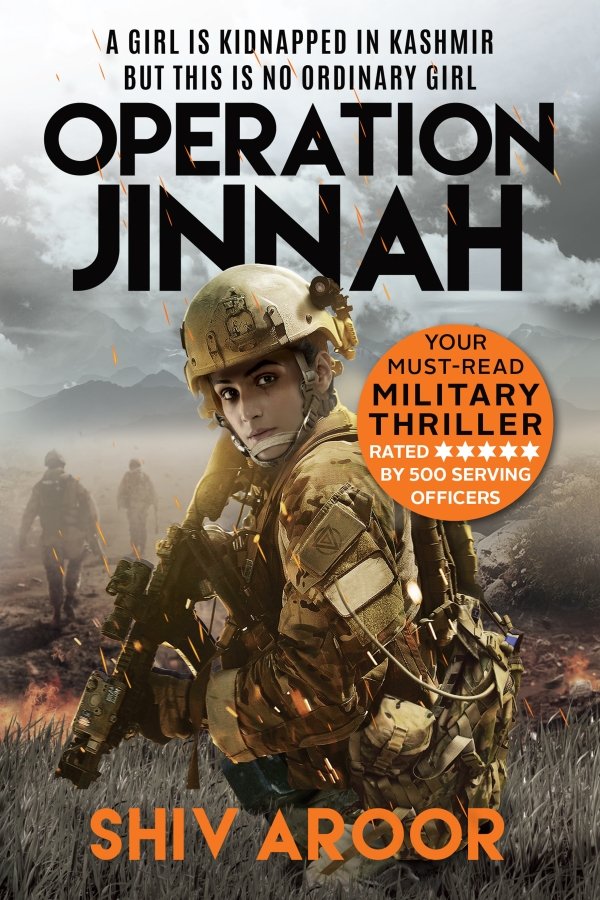

Shiv Aroor is the author of a new military thriller Operation Jinnah, available in book stores and Juggernaut.

Check Out – Best Indian Special Forces