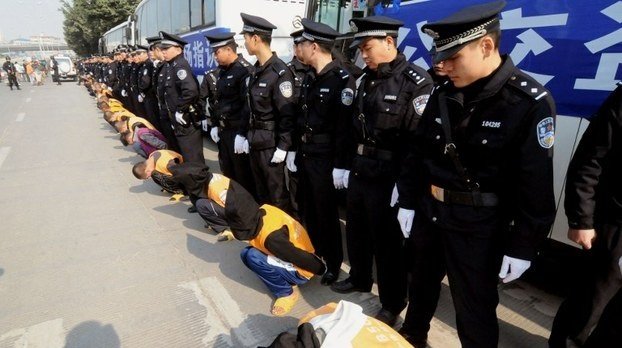

China executed more people last year than the rest of the world combined, Amnesty said Tuesday, defying a global decline with thousands of killings that have disproportionately targeted poor citizens.

Even as executions have dropped by more than a third globally, China’s death penalty rate is “shockingly high” although the full extent of the secretive practice is unknown, Amnesty International said.

While President Xi Jinping’s much-hyped corruption crackdown has seen many high-ranking figures sent to jail, their death sentences have often been commuted.

Meanwhile ordinary people caught in the crosshairs of the law have not been so lucky, it said.

Farmers were more frequently sentenced to death than any other group in China, Amnesty said in a report that sought to lift the veil on the workings of the system.

China’s ruling Communist Party regards execution figures as a state secret, meaning that hundreds of death sentences are omitted from the public database of court verdicts.

“China is really the only country that has such a complete regime of secrecy over executions,” Amnesty’s East Asia director Nicholas Bequelin said at a press conference in Hong Kong.

“Probably the reason is the numbers are shockingly high”, he added.

– Secrecy and speed –

Although local media reports estimated that at least 931 individuals were executed between 2014 and 2016, only 85 of them were found in the online database, Amnesty said.

Estimates from other rights groups also puts the number of annual executions in China in the thousands.

From arrest to execution, the process is characterised by secrecy and speed: a 2016 report from US-based Dui Hua Foundation said China’s average death row prisoner waits only two months before being executed.

Dui Hua estimates that there were approximately 2,000 executions in China in 2016, down from 2,400 in 2013 and some 4,000 in 2010 — following legal reforms that improved oversight.

Concerns over wrongful convictions have grown in recent years, fuelled by police reliance on forced confessions and the lack of effective defence in criminal trials.

Chinese courts have a conviction rate of 99.92 percent.

The nation’s top judge, Zhou Qiang, apologised in 2015 for past miscarriages of justice, saying: “We feel deep remorse for wrongful convictions”.

Public anger has mounted over miscarriages of justice, including a high-profile case that saw a teenager in Inner Mongolia wrongfully convicted and executed for rape and murder in 1996.

Hugjiltu was put to death two months after the woman was killed and was finally exonerated nine years later when a serial killer confessed to the crime.

Despite Chief Justice Zhou’s call to “correct” mistakes, experts say recent reforms have not been widely implemented.

“Coerced confessions are supposed to be excluded from evidence. In practice, however, the police have unchallenged discretion to… extract confessions by detaining and torturing suspects for long periods,” New York University professor Jerome Cohen told AFP.

Even cases which provoke widespread anger and online petitions calling for death sentences to be revoked are not exempt.

Farmer Jia Jinglong was sentenced to death for killing a village official with a nail gun after his home was demolished weeks before his wedding day in 2013.

Jia was beaten and denied compensation for his house, the state-run Global Times reported, and the case prompted fury in China, where land seizures and forced evictions of villagers by local officials have become a major source of social resentment.

But despite the public outcry and calls from legal experts to commute his sentence, he was executed last November.

Only a handful of countries still use the death penalty with regularity.

The United States executed 20 people last year, the lowest figure for the country since 1991.

All other countries together executed at least 1,032 people last year — a decline of 37 percent compared to 2015. Of those, 87 percent took place in just four countries – Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Pakistan.

(Feature image source: Reuters)