It’s been almost 12 years since the first announcement was made, in which it was stated that Sanjay Leela Bhansali would direct a film based on the historical threesome of Peshwa Bajirao, Mastani and Kashibai. Ultimately, the wait was worth it. Not just because Priyanka Chopra, Ranveer Singh and Deepika Padukone headline a superbly talented cast, but because if there was ever a time to tell Bajirao, Kashi and Mastani’s story, it is now.

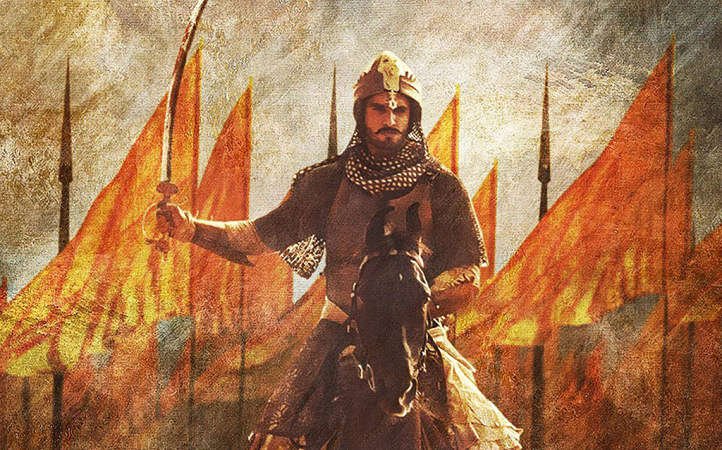

Set in 18th century Maharashtra, Bajirao Mastani is based on the story of Peshwa Bajirao and his two wives, Kashi Bai and Mastani. Bajirao was a great warrior and it was during one of his campaigns that he effectively won Mastani, the daughter of a Bundela king and his Persian wife. While Kashi was the first wife and the mother of Bajirao’s heir, the second wife Mastani proved to be something of a soulmate. She was a good enough warrior to ride into battle alongside Bajirao. Off the battlefield, she was a gifted singer and dancer.

A still from the film.

In the rigidly Hindu society of Maharashtra’s Chitpavan Brahmins, Bajirao choosing to favour Mastani over Kashi was all sorts of taboo. From the few historical records that exist, we know that Bajirao’s family didn’t approve of Mastani and tried to separate them.

Mastani was even imprisoned on one occasion, but eventually, she was released and remained by Bajirao’s side as his second wife till his last day. When Bajirao died, some say Mastani committed suicide while other accounts say she passed away soon after him. Kashi would raise Mastani’s son after Mastani’s death, even though he was raised a Muslim, which is undeniable proof that Mastani had been accepted.

It’s easy to see why this story has delighted so many writers in Maharashtra. Bajirao and Mastani’s relationship was and remains as scandalous as it is progressive. The liberalism of Bajirao, Mastani and Kashi makes this historical account startlingly modern. Today, when accusations of love jihad and communal tensions surround us, this unflinching love story between a devout Hindu warrior and a non-Hindu princess (although her son was raised a Muslim, Mastani probably belonged to the Pranami sect that didn’t recognise caste or religious divides) is one that bears repeating.

Bhansali is not known for subtlety, but the way he criticises religious orthodoxy without speechifying is among Bajirao Mastani’ s finer qualities. The director is unabashedly against anti-Muslim paranoia and he cleverly weaves his liberal beliefs into the dynamics of the love triangle and political drama.

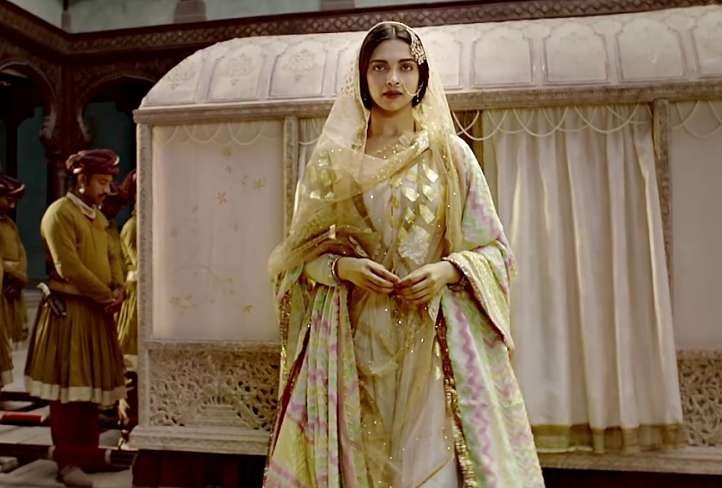

A still from the film.

Unsurprisingly, Bajirao Mastani is visually spectacular, but tottering when it comes to facts and history. Accuracy has never been Bhansali’s strength — in this film, he blithely shows Maheshwar in Madhya Pradesh and claims it’s Satara in Maharashtra — but the opulence and detail with which he recreates Bajirao’s kingdom is beautiful enough to convince most people to ignore the lack of historicity.

Bhansali has a long-standing fascination for love triangles, as is obvious from the fact that four of his eight films feature this element. He’s also fond of grandiose tragedy, where lovers must pine and be united in death. Particularly since the facts are scarce, Bhansali is free to take Bajirao and Mastani’s history and fit it into the mould of his brand of romance.

And so, like in practically every Bhansali film, the hero is a quirky but dashing gent. The heroine is feisty but elegant, wearing fulsome skirts and heavy jewellery. Their romance is doomed to have an unhappy ending, naturally. But before that final tear-wrenching conclusion, there must be elaborate song sequences, which are more important than character development, and slow motion moments that let the audience appreciate just how much was lavished on production design and costume.

To be fair to Bhansali, despite this formula, the subjects he’s chosen have covered a wider, bolder and more ambitious range than most commercial filmmakers dare. Unfortunately, despite having been in the works for so long, Bajirao Mastani stands out more as a replica than an original. Before interval, it’s strikingly reminiscent of Mughal-e-Azam .

There is a dance in a sheesh mahal , a prince meeting a courtesan-esque woman, a woman who outwits an emperor with her quick wit; and instead of a feather, there’s some bathroom activity involving paste and a shirtless Bajirao to get the pulses of all genders go pitter patter. Post-interval, Bajirao becomes noticeably like Ram of Goliyon ki Raasleela – Ram-leela and the love story becomes a variation of Romeo and Juliet, instead of exploring its own narrative.

A still from the film.

Bhansali’s tweaks history in many ways. He imposes the modern notion of monogamy Bajirao and Kashi, which wouldn’t have played much of a part back in the 18th century when more than one wife was standard practice. Characters like Kashi’s younger son disappear without explanation while the elder son pops up conveniently, just in time to be a shadowy villain who has no part to play beyond flaring his nostrils.

At one point, Bajirao gives up the his title of Peshwa to be with Mastani. You’d think that would be a big deal, but not in Bhansali’s vision, which is far more concerned with creating suitably pretty CGI clouds and moonlit sky as the backdrop for Padukone and Chopra’s dance.

Tragically, the biggest casualty of this campaign to force history into the mould of a Bhansali romance is the actual love story. Largely because of the writing, Bajirao and Mastani’s relationship doesn’t feel particularly compelling and it’s Kashibai whose pain as the wronged wife becomes the heart of the film, thanks to Chopra’s stellar performance.

She delivers her dialogues with beautiful precision and fills her silent scenes with powerful emotion. You find yourself rooting for Kashibai, almost forgetting that Bajirao and Mastani are the team you’re supposed to be cheering for and that the film is not titled “Kashibai”.

A still from the film.

In contrast, Padukone struggles to bring Mastani to life. Bhansali’s Mastani is a list of attributes, but without an emotional connection. We’re shown Mastani’s beauty, her swordsmanship and her musical talents, but somehow, they don’t all come together to give us a sense of a real person. She feels artificial and her relationship with Bajirao isn’t really explored. We see Kashi and Bajirao’s relationship build and break down, but in contrast, the love affair with Mastani is made of only bombastic dialogues and regular hugs.

Singh looks fantastic as Bajirao and it’s difficult to imagine another man who would be able to carry off that thoroughly unflattering hairstyle as well Singh does. However, while Singh is charismatic as the Peshwa and warrior, when Bajirao Mastani turns its attention away from battlefields, Singh is less majestic. It probably doesn’t help that Bhansali keeps making Bajirao walk into pools as though Bajirao was hoping he’d have a Jesus Christ moment and be able to walk on water. Either that or Bhansali figured that rather than risk raising the censor board’s censure, he’d show Bajirao and his lady loves literally get wet instead of showing their attraction towards one another.

In addition to his three stars, Bhansali has some talented actors in the supporting cast, like Tanvi Azmi as Bajirao’s mother and Vaibbhav Tatwawdi, who plays Bajirao’s brother Chimaji. Everyone overacts, but evenly, which gives the film the consistently flamboyant tone that has become Bhansali’s trademark.

With history as its starting point and a director like Bhansali who has enough of a standing to make a lavish and unconventional film, Bajirao Mastani could have been brilliant. Instead, it’s just average, with gorgeous spectacles and some fine acting, but not enough heart and too little passion. For a love story directed by a romantic, that’s a shame.

(All images from the film’s official Facebook page)