Shopian: The killing of the most wanted Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) commander Abu Qasim last Tuesday reminds one of a famous saying: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.”

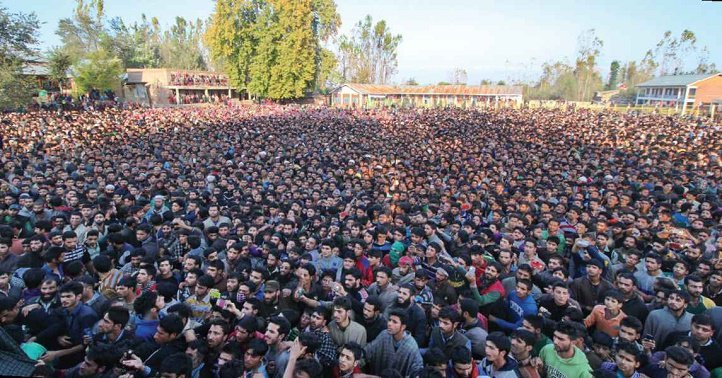

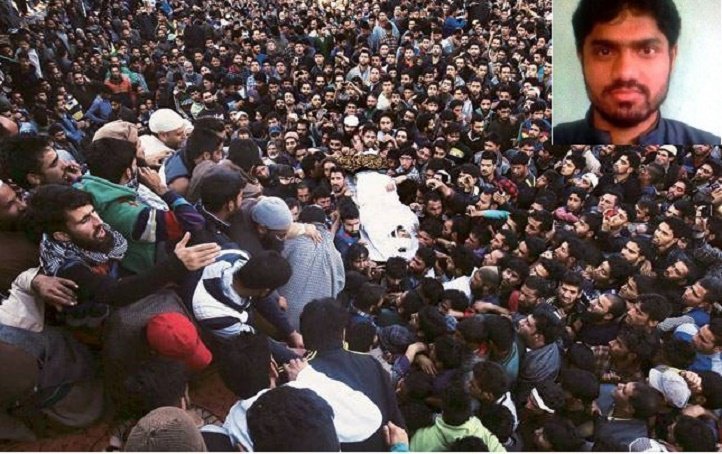

The thousands who turned up for his funeral procession was reminiscent of Yakub Memon’s last rites in Mumbai a few months back. A court had found Memon guilty of being involved in the 1993 Mumbai blasts and higher courts had reaffirmed the verdict. Yet, the people turned up in droves. And seemed proud.The police have said Abu Qasim’s killing is a big achievement; one that has broken the back of militancy in Kashmir. But after Qasim’s death, the narrative on the ground, especially in south Kashmir’s Kulgam area — where he was laid to rest — paints a radically different picture. The turnout for his funeral indicates that he was a hero to many.

“It is just out of love. He might have been a most wanted ‘militant, terrorist or whatever the name police gives him’ but for me, he was a Jihadi, a loved person, who had come from Pakistan to liberate us. We wanted to bury him in our own village, but the people of Bugam didn’t agree. They resisted our claim,” said a local pleading not to be named.

While many of us may find the statements to be rather incredible, it is the ground reality. Peace in Kashmir has always been fragile — it never took much to break it. It all started way back in 1990s when a massive armed struggle started in Kashmir seeking freedom from the Indian state, but then things settled down. But after a lull of over a decade, militancy is back, and deadlier than ever.

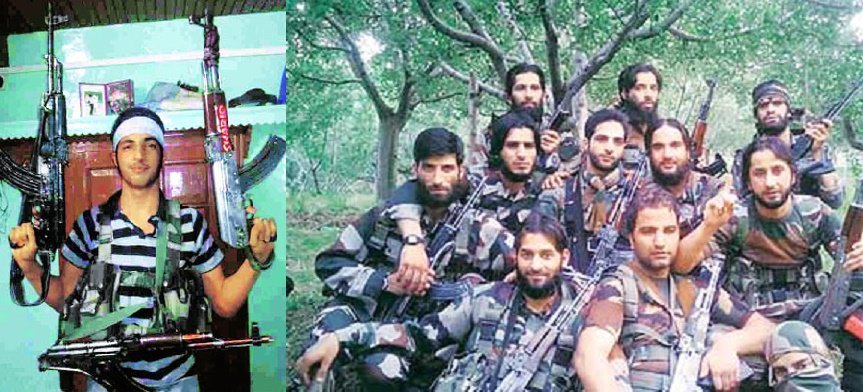

This time there are more locals and fewer foreigners involved — and that should be a big concern for the security establishment . This new breed of militants seem to be more committed to their only goal of martyrdom. From Facebook to Twitter, photos of these tech-savy militants are everywhere — sporting modern outfits, taking selfies, flaunting guns, etc. They are not afraid of being seen; not any more.

Many in the Valley, silently, see it as a return of the 1990s era. And if it is so, things could scale up rather quickly and it would become dangerous for everyone.

Some militants, also reportedly joined Qasim’s funeral procession and offered a three volley salute with guns, much like the style employed by terrorists to former comrades in the 1990s.

People from different villages fought for the right to bury Qasim in their village. They wanted to bury the Pakistani militant in their respective villages.

Even people from other districts like Pulwama and Shopian wanted the body to be buried in their villages. The basis of the claim, a local at Bugam village said, is simple: Abu Qasim had spent more time in their areas.

For four days after the killing, Indian forces were forced to have a shutdown in place to maintain calm.

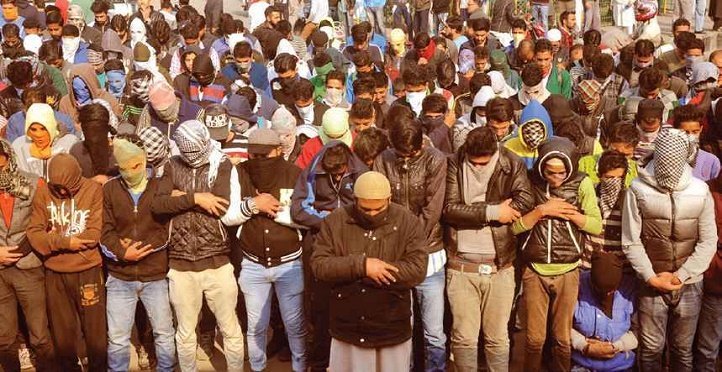

People, especially teenagers, were on the roads, pelting stones at security forces. Similar scenes were witnessed in the volatile Nowhatta area of Srinagar — which has remained the hotbed of militancy, and a pro-freedom bastion since 1990.

There were no vehicles on the roads three days after Qasim was killed. We reached Kulgam town on a motorcycle, where a group of youth suggested ‘it was better to walk on foot.’

We spoke to some youths shouting pro-freedom slogans at Kulgam town, who appeared to be very angry. But upon seeing a camera, they became more cautious.

They refused to talk. “You won’t write what we will tell you. They are our heroes and you (mediamen) write them off as terrorists. Why should we talk to you then,” said a group of youth who had covered their faces with white scarves.

They hinted that it was perhaps better we left before things got too dangerous. If there was ever a sign to get going, this was it.

There are many factors that could throw Kashmir back to turbulent 1990s.

First, the increasing wave of perceived intolerance in India has already enraged many Kashmiris. People in this conflict-ravaged state have been appalled by what they see as the targeting of Muslims in India. The BJP harping about the abrogation of Article 370 – which gives J&K; a special status in the Indian Union – hasn’t helped .

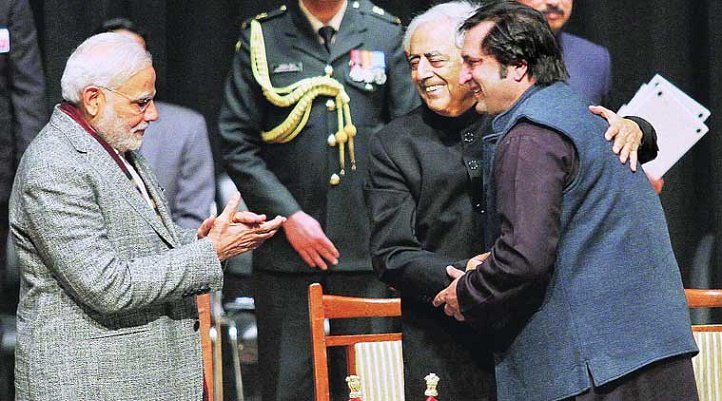

Just a day after Abu Qasim’s killing, J&K; chief minister Mufti Muhammad Sayeed reiterated that no one could dare tamper with Article 370. But these factors have only stoked fears about Kashmir’s association with India.

Second , the disappointment with the Mufti-led coalition government has reached new highs.

Mufti’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP) had earlier said that a major reason to form the government with the BJP was to ensure the delivery of a major flood relief package from central government. But six months later, the PDP is still to get any package from the Centre.

People are now bitterly accusing the Mufti government of betrayal and allowing ‘communal groups in the state’ to flourish.

The hero worship of Abu Qasim – and the implied acceptance of LeT’s fundamentalist ideology – perhaps just another sign of this resentment.

Critics of the Indian state say that all these signs show the two-nation theory, which warned Muslims about the dangers of accepting composite nationhood in a Hindu-majority India, was right. The government will need to move decisively to put an end to this sentiment or it could have dangerous repercussions.

Read more: