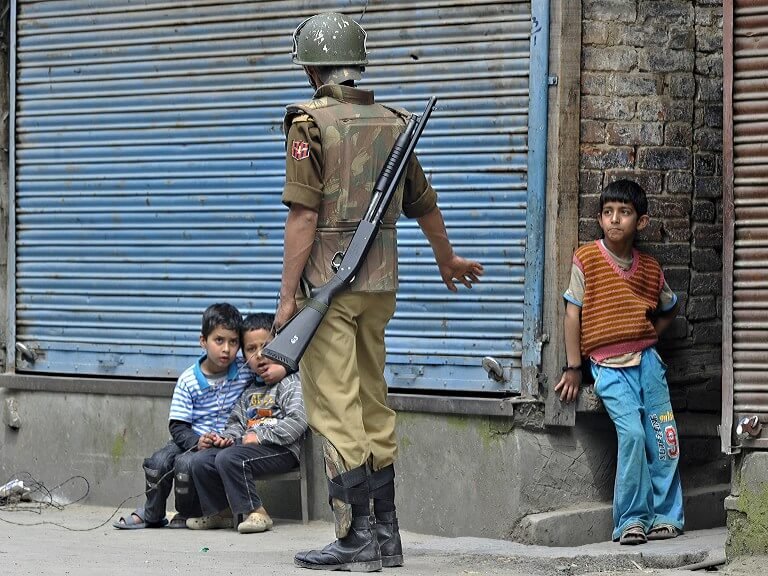

Like pretty much everyone else, I hadn’t anticipated the kind of overwhelming public outrage over the killing of popular Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Muzaffar Wani. Young boys becoming militants and dying in encounters is almost routine in strife-torn Kashmir. Wani’s death sparked something different.

When I landed at Srinagar Airport on an early morning flight on July 12, at least 15 civilians had been killed in firing by security forces in the three days after the militant’s killing.

I had deliberately booked an early morning ticket for home, hoping the troops and policemen entrusted with the job of enforcing curfew wouldn’t be out that early. My guess was correct, but still I couldn’t go home. My friend, who works with a local media outlet, had left Srinagar’s Press Enclave before sunrise to reach airport.

He was the only person I had informed of my return home. I wanted my family to believe that I was still in New Delhi – far and safe from the rain of pellets and bullets.

We drove directly to my friend’s office. Staying in the hub of media outlets of Srinagar was perhaps the best way to stay connected with the happenings in valley during curfew.

While Kashmir was facing an internet ban and had no mobile phone service, I was one of the few privileged ones. I had access to internet through broadband and I was able to use a landline phone.

But I had to be on the ground to report. I had to walk miles for a single quote after other phones went dead.

Many may not know it, but Kashmiris have always been wary about the coverage of events in the state by New Delhi and Mumbai-based media outlets – particularly television news channels.

But this time, the opposition to the media was even more evident. Even local journalists were not spared. People just wanted the media to vanish.

A pellet victim, his head wrapped in bandage, asked me for my identity card before he told me what happened to him. His friend told me that they are afraid of CID members profiling victims.

Another young victim’s father told me that his son was injured by a stone that ricocheted off a vehicle’s tyre. However, his X-ray on a table next to his bed clearly showed a number of pellets inside his head. I didn’t probe further.

Initially, no journalists had access to South Kashmir. In Srinagar, the only reports journalists could file were those about the rising death toll and number of injured.

After a week of failed attempts to reach South Kashmir, I finally made it to the epicentre of the violence. But despite being accompanied by two senior journalists, I was almost beaten up by angry youth on nearly half a dozen occasions.

We were abused, labelled “Indian agents” and called names. They also snatched the banner identifying us as journalists that we had fixed on the windscreen of the vehicle we were travelling in.

They were not angry at the lack of coverage but the misrepresentation and lies about them.

When we went to meet the family of a 15-year-old boy killed by CRPF firing in Kulgam, the protesters didn’t allow our vehicle beyond a point. We were told to go the rest of the distance on foot. We did.