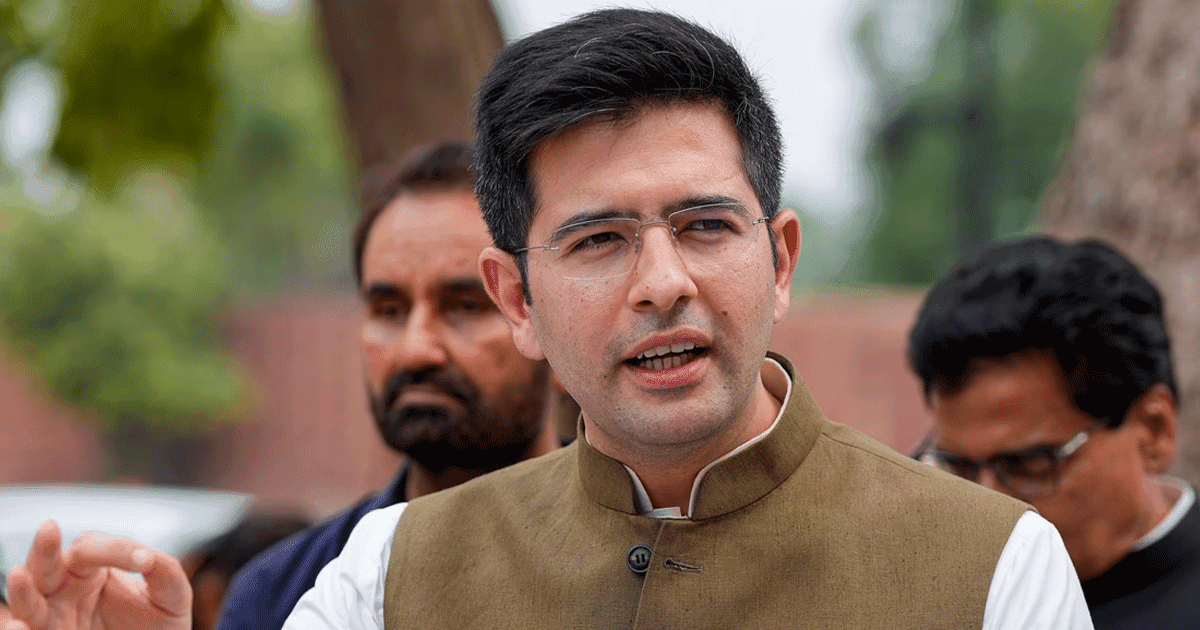

This February, Raghav Chadha stood up in the Rajya Sabha during Zero Hour, and it was a wow move. His words were few but sharp and stern, and certainly enough to stir a core idea about democracy. Since voters pick leaders, should they not also be able to dismiss them halfway through a term when performance lags?

That thought took shape as a push for a nationwide Right to Recall, which is a mechanism to ‘de-elect an elected representative, before their term ends’.

He backed it with online examples, global models, checks to prevent misuse, along with concerns over how well the Union Budget addressed employment. It was a brief moment as he stood up and expressed his concerns, but somewhere between his words, the weight of the parliament shifted.

Out of nowhere, Raghav Chadha kicked things off with words that race through feeds everywhere now. The idea was that voters who pick a politician must also hold power to remove them.

“If voters can HIRE a neta, they should be able to FIRE the neta too.

If Indian voters have the Right to Elect, they should have the ‘RIGHT TO RECALL’ too,” his post read.

“If we can impeach the President, the Vice President and judges, and move a no confidence motion against an elected government mid term, then why should voters be forced to tolerate a non performing MP or MLA for five full years,” it further specified.

On X, once called Twitter, he sketched how such a recall should work. A set number of verified signatures would kick it into motion, but not right after an election though, there’d be a waiting window first. Only solid reasons like fraud, proven corruption, or deep failure in duty could justify it, and then the last step should look like this; a public vote needing support from over fifty percent to make dismissal real.

Now pulling someone from the office isn’t usually done lightly where democracy has deep roots. In places like these, rules often demand strict steps just to start the process, keeping emotions or grudges from driving decisions. Take the example given by Raghav Chadha, he said that over two dozen democratic nations already let voters remove leaders under certain conditions.

Countries such as Canada, the U.S., and Switzerland appear on that list, proving systems exist to balance public power with built-in checks.

A request came from Chadha afterwards. This one linked directly to the Budget, it may have seemed out of place at first. But his argument deepened the scale, and suddenly the dots felt more connected than ever.

Not just tossing out a catchy phrase, Raghav Chadha turned the chamber into a space where governance came face-to-face with real lives. With youth unemployment hitting 3.1 crore, he asked straight, what slice of spending actually builds work for them? That number was telling and eye-opening, it was a mirror held against broken pledges. What simmered beneath each word was clear, as trust erodes when leaders dodge blame, whether for flawed plans or personal slips. Because jobs are on thin ice, he stood up when budgets got discussed and sought a connection between promises and paychecks.

His view is that recall should push for better results, not only serve as punishment. That thought led Raghav Chadha to suggest waiting eighteen months first. This gives reps space to show what they can do. Getting the process started needs backing from between thirty-five and forty percent and only then, does voting begin. To actually oust someone, more than half must agree in the end. Barriers stay high early on, which keeps pointless attempts away and the last step stays hard too; making sure firing someone means real public demand.

Out of nowhere, things got a little intense after Raghav Chadha started speaking and wait, he was not alone. Videos popped up fast, showing voices rising in the hall. Jaya Bachchan cut in, her sharp statements flying over how speeches should be delivered, and what counts as proper conduct. She said, “If given time, I can speak without looking at the paper.”

The parliament’s atmosphere surely heated up at this statement. It stalled everything on the floor, just for a beat. Clips spread like smoke through phones and screens and then more eyes landed on what Chadha had actually said, and how tight the air felt among members that day.

International precedent: How recall has worked

Take the 2003 California recall, because that moment stands out. Governor Gray Davis left office after a wave of signed petitions, far beyond what the rules demanded. Then came a vote, over half supported his removal, specifically 55.4%. What followed was a new leader; Arnold Schwarzenegger stepped into the role. Raghav Chadha points here to make sense of bigger ideas and a kind of power shift that shows something authentic and rooted in the very ordeal of democracy.

Nowhere does it say India lacks tools for recall elections. Raghav Chadha pointed out that some states allow them in village councils. Other nations do too, yet, these options vanish once you reach state assemblies or Parliament. The system knows the idea well enough, but just refuses to apply it higher up.

India faces constitutional and practical challenges

Getting rid of elected lawmakers before their term ends means building new legal structures from the ground up. In certain parts of India, local councils already let voters remove representatives early; yet no rule exists across the country to oust members during assembly or parliament terms. Setting up a nationwide process must face troubles like rights written in the Constitution, laws stopping politicians from switching sides, how votes are checked digitally, and election tech readiness, on top of power dynamics inside parties that control who runs and stays loyal. Experts warn that the real difficulty lies in crafting rules tight enough to block abuse while still letting public voices be heard.

But not every party will greet a nationwide recall rule with open arms. Where leadership tightly manages candidates and expects loyalty in parliament, such a change might feel like an unwelcome facade. Some groups however could embrace it, seeing a chance to stir voter energy and show they listen. Raghav Chadha’s idea works both as a practical fix for how leaders respond to people, and as a strategic move to reshape expectations before ballots are cast again.

Next up may be a path that might wander straight into legal steps, or maybe nowhere at all.

Speeches in Parliament or posts online might shift how people talk about politics. Turning the Right to Recall into actual law needs review by committees, agreement across parties, and checks under the constitution. Chadha has pushed this topic into view nationally. If it becomes legislation, or just fades as election chatter, hinges on talks between parties and what voters demand. For now, his push for elected officials to answer through recalls, paired with sharper results in job-related spending, will keep holding ground.