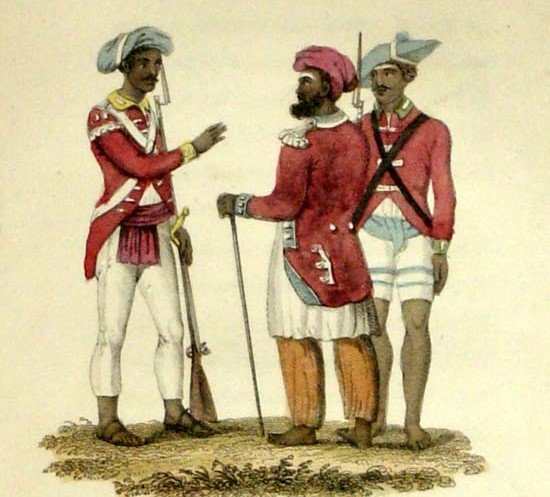

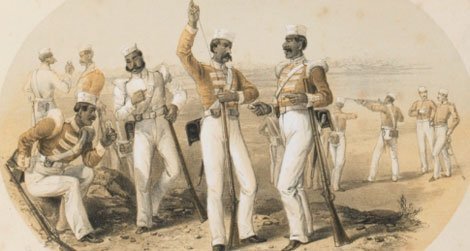

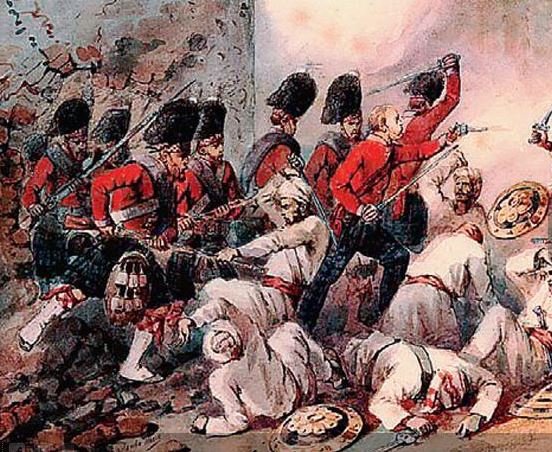

The revolt of 1857, or the Sepoy mutiny as we know it, was India’s first war of independence from the British rule. Our soldiers weren’t as well equipped as the British army and yet they fought with all their might and laid down their lives fighting the oppressive British policies.

But how did it all begin? How did our soldiers strategize at a time when modes of communication weren’t as fast as they are today?

Some historians believe that a few months before the uprising of 1857, a mysterious distribution of chapatis (roti) began which nobody was able to explain.

It was Mark Thornhill, the magistrate of Mathura, who noticed this first in February 1857. One morning, when he entered his office, he saw 4 “dirty little cakes of the coarsest flour, about the size and thickness of a biscuit” lying on his desk. Upon inquiring, he was told that a watchman had handed them to one of his Indian police officers.

Upon further investigation, it came to light that this had been going on at a lot of other places as well. Someone would come from the jungle, hand over the chapatis to the watchman with an instruction to make 4-5 more of them, and pass them on to the watchman of the next village. The watchmen usually travelled with the chapatis hidden in their turbans.

But nobody knew where they were originally from or what they meant.

The chapatis were being distributed at an alarming speed.

As noted by Thornhill, the supposed ‘culinary letters’ were being distributed at a pace of somewhere between 100-200 miles a night, which was faster than the fastest British mail!

Clearly, the locals were just as baffled by the distribution. While the British thought that the chapatis bore some kind of secret message with an agenda against them, the locals were scared because of rumours that the British had sprinkled the blood of cows and pigs in the salt to mess with Hindu and Muslim religious sentiments.

Fearing that breaking the chain would result in something terrible, the local communities continued to pass on the chapatis, without any substantial knowledge about the cause.

The fear in the British about this unknown movement is evident from a letter Dr Gilbert Hadow wrote to his sister in Britain in March 1857. He wrote:

There is a most mysterious affair going on throughout the whole of India at present. No one seems to know the meaning of it. The Indian papers are full of surmises as to what it means. It is called ‘the chupatty movement.

Some officers believed that the chapatis contained concealed seditious letters. On the 10th of May, the first regiment mutinied in Meerut, after which other regiments followed suit.

Later, when the British examined the cause of rebellion, they couldn’t ignore that some kind of systematic cooperation was going on among the people for a united purpose and that all of this couldn’t have been spontaneous.

It was believed, in retrospect, that the rapid distribution of chapatis was a warning about imminent trouble and that it was set in motion by some people who were conspiring the mutiny months in advance.

Even today, nobody knows about the origin of the chapati movement and the purpose behind it, but it certainly caused a wave of terror in the British camp as well as amongst the local people!