During the ongoing Jio MAMI film festival, Lipstick Under My Burkha director Alankrita Shrivastava sat among a panel of 5 directors, as the only ‘female director’. Hence, it was hardly surprising when a question came as to why there were such few female directors in Bollywood. “I could write a book on this question,” said the director who has only made two films in more than a dozen years.

Alankrita Srivastava is actually an exception to the rule, who survived the failure of her debut film Turning 30 which came out in 2011. Many female directors/technicians hardly get a second chance, where they’re living and dying by the sword of that first film.

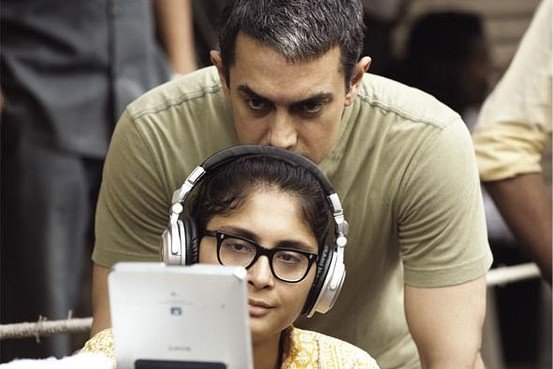

“We don’t just need more films made about women, but also more women making films.” #KiranRao at #WomenInFilmBrunch #OxfamAtMAMI pic.twitter.com/sCMJ6HbJDF

— JioMAMIwithStar (@MumbaiFilmFest) October 16, 2017

The fact that Bollywood is sexist, misogynistic and sees women in few, specific roles has been observed since the beginning of time. The sad reality is that things have hardly improved, even in 2017. The problem is nuanced, and there is a need to identify the main triggers.

The trade talk surrounding ‘women-centric’ films (pronounced like a bad word) isn’t very pleasant, and the general consensus is that these films don’t make money. Despite having been proved wrong time and again with films like Kahaani, Queen or Pink – the trade continues to see these films with skepticism.

Kiran Rao, who made her debut with Dhobi Ghat in 2011, has stayed away from direction owing to the film’s less-than-favorable box office collection.

She reiterated Alankrita’s point saying there was not only a need to make more films about women, but also a need for women to pick the camera up to tell their stories – at the ongoing MAMI festival 2017. There are always the exceptions to the rule – like Farah Khan and Zoya Akhtar.

Farah made a superhit debut with Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Main Hoon Na in 2004. Zoya, in spite of a stellar debut which met with a lukewarm response at the box office, has gone on to make ‘hit films’. Not taking away from their talent in any which way, the road is slightly easier for a Bollywood insider compared to women who have absolutely no backing, financial or otherwise.

Most women professionals in Bollywood do not have the privilege of knowing actors, writers and producers, which does not allow them to move on from a Luck By Chance or a Tees Maar Khan. Someone like a Rajashree Ojha didn’t get another opportunity after Aisha.

Do we have female-led films? Or a film where at least 50 per cent of the key creative roles: writer, director, producer and protagonist (lead character) were helmed by women?

I can only think of Sneha Khanwalkar working as a mainstream music composer. There are nearly no female cinematographer or sound-recordist working in mainstream Bollywood. The film industry has names to reckon with, but there are only a few and far between. Only a few women like Guneet Monga and Rhea Kapoor are calling the shots of a production house.

In an industry which produces more than 3 films a day, the number of female technicians can be counted on one’s fingers.

And if this isn’t sad enough, the role of a female actor, which remains the most ‘respectable job’ for women in Bollywood, remains quite vague. Rarely do we see fractured portraits of female characters as in Simran or NH 10.

When it comes to finding more positions for women, Bollywood remains a rather unwelcome place. However, the rise of Gauri Shindes and Zoya Akhtars seems to suggest there is a change in order. The gender balance may be shifting slightly, but there is still a long way to go.

However slow and gradual, the first step to solving the problem lies in acknowledging it. The lack of women working in Bollywood is a problem – now we need to go ahead and solve it.