As far as the Hindi film industry is concerned, the past decade (2010-19) has been an important one, in terms of content, the emergence of debutant voices, and the change in mediums of entertainment consumption (and distribution).

However, this was also the decade that shown a spotlight on female voices in the industry, and perhaps, for the first time in years, the industry’s gender representation wasn’t completely skewed.

From actors to directors, technicians to producers, women have been an intrinsic part of the Hindi film industry since the start. However, barring few actors and prominent directors, most of them were not given the credit and attention they deserved.

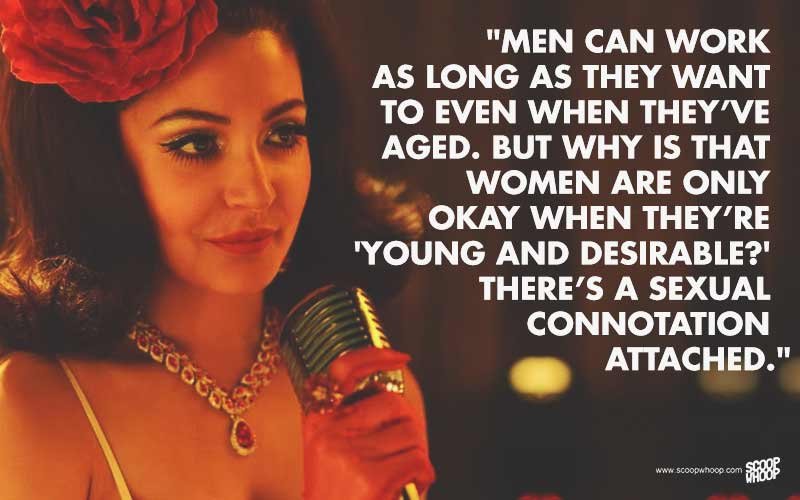

To begin with, female actors often had to battle (or worse, accept) pay disparity, a ‘shelf life’, and illogical notions such as marriage and pregnancy meant the end of a career.

And while these ideologies still exist in the industry, the past decade saw more and more voices challenging and debunking them.

Most of us millennials grew up watching the cinema of the late 90s and early 2000s. This meant that our major view of female characters was as the hero’s love interest, family member, or the vamp. This is not to say that diverse female characters didn’t exist, but they were few and far in between.

Especially in the case of commercial cinema, where even stories with unexpected plotlines showcased unidimensional female characters.

But the past decade saw on-screen female representation shift. From treating female characters as co-leads in romantic dramas and comedies to helming complete movies on a female actor’s able shoulders, gender representation saw visible and wonderful changes.

More importantly, it wasn’t just ‘female-centric’ movies or ‘indie films’ where a female-led story worked.

From thrillers to slice-of-life films to action-dramas, the stories worked with a female lead and resonated with all kinds of audiences.

Additionally, even as female leads, there was diversity with respect to the characters and actors. Simply put, actors of all ages played characters from different backgrounds.

And finally, the ₹100 crore club was no longer dominated by just male superstars (or a set pattern of stories).

Secondly, even behind the camera, female voices took center stage. We had debutant and seasoned female directors deliver films that were the perfect mix of powerful stories, great performances, and expert direction.

Movies directed by female directors and/or written by female writers became the representation of the millennial generation. Case in point, Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara.

For Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti to take a theme as common in the film industry as friendship (especially male friendship), and still deliver a timeless movie is proof of their genius.

And the female gaze that they lent can easily be attributed as one of the reasons that allowed movies on diverse themes, like family problems, gully rap etc., to resonate with all sections of the society.

Similarly, Gauri Shinde’s English Vinglish and Dear Zindagi were ‘commercial hits’, but not based on topics one would traditionally consider to be commercially viable.

Just like Meghna Gulzar’s Raazi displayed a brand of patriotism that felt more honest than most other films that talk about love for the nation. Or Nandita Das’ biopic Manto, that actually felt like an authentic portrayal, rather than a falsified, whitewashed version of a famous personality.

At the same time, female writers gifted Indian cinema films that were like a breath of fresh air. Be it then Kamna Chandra’s Qarib Qarib Singlle, or Konkona Sen Sharma’s Death in the Gunj (who also directed the film).

Another point to note was that contrary to what a section of the society perceives, female writers did not just write about female issues. Case in point, Juhi Chaturvedi’s entire filmography (Vicky Donor, Piku, October, The Sky Is Pink).

And it wasn’t just about writing, direction, or acting. We had female backed production houses that gifted Indian cinema films that were definitely not your run-of-the-mill stories.

As producers, these actors backed important projects and ensured that certain creative voices did not get lost in the deluge of mainstream but mediocre cinema. Like the National Award-Winning Marathi film Paani that was produced by Priyanka Chopra’s Purple Pebble Pictures.

Or Oscar-Award winning documentary, Period. End of Sentence, which was produced in part by Guneet Monga, who incidentally, also co-produced the Gangs of Wasseypur series, Masaan, The Lunchbox, etc.

Similarly, film editors like Pooja Ladha Surti (winner IIFA award for Best Editing, Andhadhun), Deepa Bhatia (My Name is Khan, Kai Po Che!, Fitoor etc.), or Aarti Bajaj (Rockstar, Tamasha, Sacred Games etc.) firmly established their presence, even in a primarily male-dominated field.

In fact, Pooja Surti has been the editor for most of the thrillers that Sriram Raghavan has directed. And it is a fair assumption that for any thriller, editing has a crucial role to play.

What is interesting to note here is that in an industry that is notorious for thinking a woman’s career ends after marriage (and/or pregnancy), we had multiple female actors who convinced the industry (and the audience) why this notion needs to be laid to rest, once and for all.

And lastly, it was web series that truly proved to be the game changers of the decade, for all artists (writers, editors, directors, and actors).

From allowing greater freedom of expression to giving a chance to debutant artists to shine and prove their worth, web series at least appeared to be a platform where talent took precedence over gender.

Additionally, web series and short films also gifted us female characters who were anything but unidimensional. We had characters who were bold, conflicted, relatable, and powerful.

The only thing these characters were not is ‘conventional’. And that truly made for a refreshing change.

It’s not as if Bollywood had not given a platform to female voices in the past. But for the longest time, there was a clear demarcation of who was a ‘commercial actor’ and who was an ‘indie actor’, especially when it came to female actors. This was the decade that those lines finally started blurring.

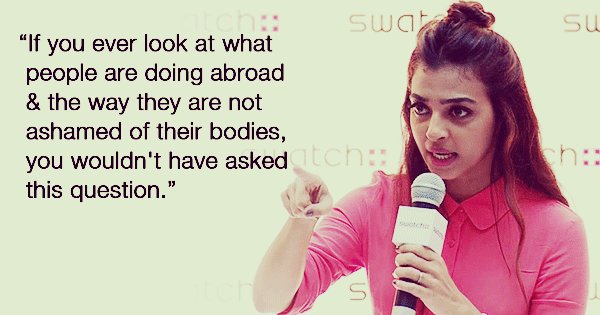

This was also the decade when many mainstream actors took on issues (within the industry and in general) that were, for the longest time, brushed under the carpet.

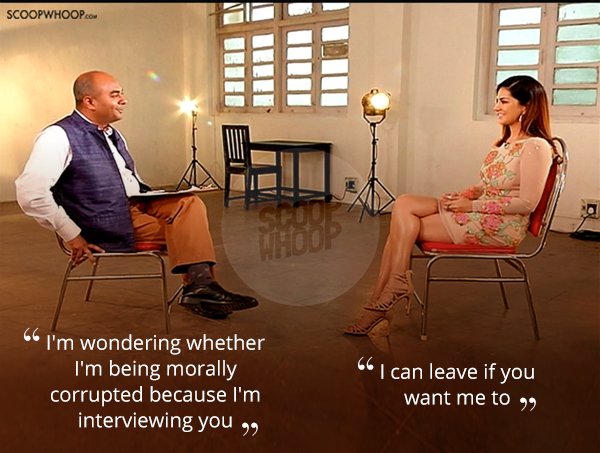

Then whether it was calling out their co-actors, standing in support of other actors, not letting misinformed journalists get away with biased questions, or simply, throwing light on pay parity and nepotism, actors no longer just accepted regressive practices as the norm.

The Hindi film industry has a long-lasting influence on the general public. Whether directly, or in a more subtle manner, but the thoughts that movies promote and the representation that films showcase does make an impact on the people. Which is why, while things are far from ideal, the change that has been visible in the past decade is one that we wholeheartedly believe in.