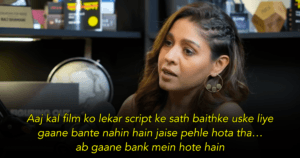

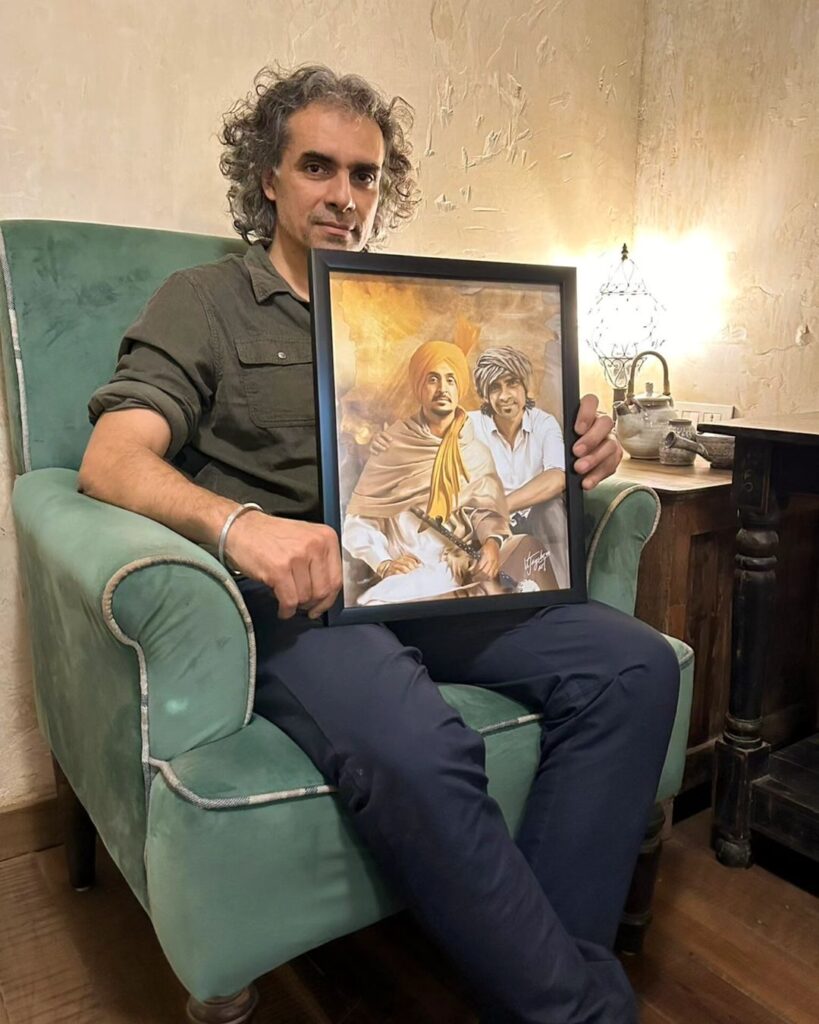

When underrated things turn mainstream, the first thing we do is lose trust in them. If not, we don’t find the need to appreciate them enough. Liking them becomes mainstream, as well; and not in a good way. At times, artists succumb to the pressure of creating work for mainstream audiences, when they started out on a different path. It’s normal to get stuck in finding that balance – anyone would. Imtiaz Ali’s recent work with Amar Singh Chamkila felt like a nudge to trust the director and his process again. Also, to not shy away from appreciating him just because everyone else is doing it too.

Chamkila is a person. In the film, he’s this world that had existed, and another one that the director created. So we not only get to witness the life and music of Chamkila, but see things beyond that. The Imtiaz Ali way of doing things, that I’ve always liked is the fact that he cares about his stories. He falls in love with the mere process of telling it, which is not the same as falling in love with the protagonist – it is in fact, better than that. For a life like Chamkila’s, facts can never be enough. What I like about Imtiaz Ali is that he has always understood that; that facts are too binary for the grayer world.

He creates work that feels personal, it’s always something you’d want to sit with. For me, Tamasha was the last time I felt that. I will not talk about the misses because that’s the easier thing to do. And when you rarely get something as good as Amar Singh Chamkila, it’s better to focus on the good. This is about the good work. More than anything, this is about Imtiaz Ali falling in love with a story, again. And when you love something unabashedly, you’re bound to be good at it, because you will always be fair to it. He’s fair to Chamkila.

So there’s this biopic that shows a good amount of research, but on the other hand, there is this parallel that runs on empathy. You are told that the singer’s music was controversial. But you’re also told that life wasn’t always fair to him – that he didn’t get to pick between the right and the wrong. The protagonist is flawed like most of Imtiaz Ali’s characters – which is a good thing for a subject like Chamkila. You are told things, you are never told what to feel about him, which is the perfect line for cinema. That’s what makes Imtiaz Ali different from most directors of his time. His heroes are not so much heroes, they are people.

The thing with almost all his films is that they run on emotions, and not technicalities. Like the Rumi quote from Rockstar: “Yahaan se bahut door, ghalat aur sahi ke paar, ek maidan hai, main wahaan milunga tujhe.” When you see the director’s films, you know he’s not trying to convince you to feel a certain way. He just wants you to watch it, and go with what works for you. He’s just being, and he wants you to be too.

There was a time when Tamasha was underrated, then we started appreciating it and people would come out with their versions of what the director wants to say. The director may or may not have meant it, but the fact that it became an almost personal piece of work says so much about the work itself. Now, with Amar Singh Chamkila, that feeling is back again. Music is both the soul and the foundation of the film – surely because it’s based on a musician, but also because Imtiaz’s work is usually driven by it. And when he gets that right, it’s a treat.

Chamkila, however, is a treat because there’s clear effort attached to it. It’s almost as if Imtiaz Ali wanted to be so honest to this one film, that he put the effort that would make it evident to his viewers. His constant perception of art and artists is visible. Amar Singh Chamkila is what it is because Imtiaz Ali is back – back to his own ways and forms of presenting a story.

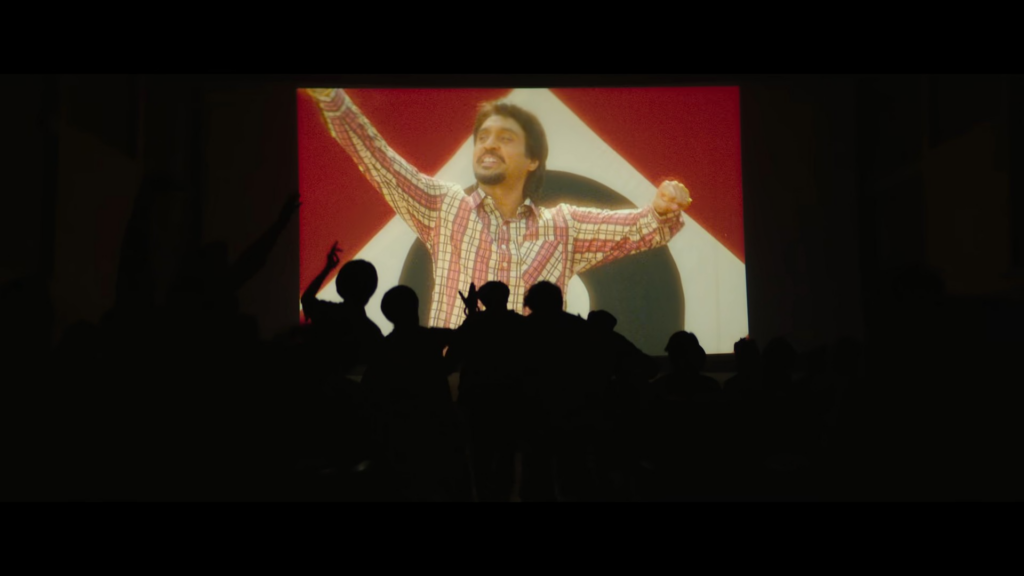

When I watch an Imtiaz Ali film I like to notice the smaller details – like how a specific scene plays out. It’s because Imtiaz Ali directs how he thinks. That part of the process makes it more honest as a visual. In Amar Singh Chamkila we just get to witness more of that. For instance, the animated sequences, the breaking of the fourth wall, and even the use of smaller elements like old pictures fit in the fictional frame, make it more raw. From Imtiaz’s point-of-view, we see Chamkila’s work. But this one is also the discourse around separating the art from the artist – or a question around if we need to – or if at all it’s possible.

As someone who has always looked forward to Imtiaz Ali’s work, Amar Singh Chamkila feels worth the wait. When a story is so layered and emotional, it’s hard to look at things objectively. For me, Amar Singh Chamkila looks like Imtiaz Ali’s comeback to his type of cinema, because he sees Chamkila more than a subject.

Chamkila is to Imtiaz, what music was to Chamkila. He loved his music, like Imtiaz loves his stories.