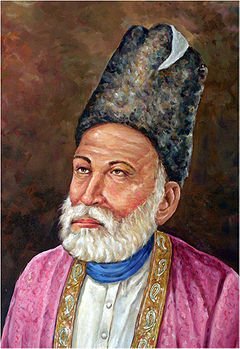

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, the greatest Urdu poet of all times, described love, heartbreak and unrequited feelings like no one else did. Even more than a century later, his shayaris still make perfect sense to us millennials.

A liberal Muslim, Ghalib was a free-spirited man who lived right next to a masjid, yet hardly ever paid a visit. Such was his philosophy of life that even though he spent his day drinking and attending mushairas, he felt a deep connection with the almighty. Ghalib struggled throughout his life but he was aware that with his rebellious writing, he was paving way for the future generation.

What most of us aren’t aware of is that Ghalib also brought about a groundbreaking change in letter-writing in that era. Before Ghalib began writing letters in Urdu, they were traditionally written in Persian. The exchange of letters was predominantly formal with people using highly ornamental language and greeting each other with complicated salutations.

His Urdu letters were published in Ud-i-Hindi a year before his death, in 1868. He wrote a lot of letters to his friends, patrons and disciples from all around the country. Ghalib’s letters give an insight into the poet’s dynamic personality, his innovation in creating a new style of writing and his thoughts on spirituality.

Published by The Hindu, below are excerpts from a few of his letters, selected and translated by Professor Taqi Ali Mirza from Hyderabad.

Letter to Mirza Hatim Ali Mehr

Mirza Sahib, I have invented a style of writing that turns a letter into a dialogue. Talk with the tongue of your pen from the distance of a thousand kos. Enjoy the pleasures of union in times of separation. Have you sworn not to talk to me? Pray tell me why have you not sent me a letter for years? You have not written about your welfare, nor have you sent me books….

Letter to Saaduddin Khan Shafaq

What wisdom is this that I write to people of wisdom in this manner? No salutation, no epithet of honour, no greetings, no humble supplication. Listen Ghalib, give up the ways of a courtier, for even Ayaz knows his limitations. Granted that after a lapse of many years I have written two ghazals of nine couplets each, but what is this way of writing? Write the salutation first, then offer your humble greetings, then enquire about welfare with folded hands, then offer thanks for the letter. Only then say what you imagine has happened …

Letter to Munshi Hargopal Tufta

I consider the philosophy of Avicena and the poetry of Nazeeri to be of no use, profitless and vague. In order to live, all we need is a little freedom from care. The rest – knowledge and power, poetry and sophistry – are all futile. What if there is an avatar among Hindus and a prophet among Muslims? What if one attains fame in life, or does not? Just enough money to be able to live, and good health – all else is emptiness, my dear friend….. I listen to people and answer their questions as should be done. I deal with everything the way it needs to be dealt with. But I know that all this is nothing. This is not an ocean – only a mirage. This is not existence, but only an illusion of existence. You and I are fairly good poets. May be we will attain fame like Saadi and Hafiz. What did they gain by attaining renown? What will we gain by becoming famous?

Letter addressed to Munshi Nabi Baksh Haqeer

Before I describe what really happened here at the time of Eid, first you tell me about the incidents in Kaul (Aligarh). People are talking about it everywhere. It was said there was rioting in Aligarh, and a score of people were killed in the fighting between Hindus and Muslims. I know that a similar report would circulate about Delhi. But, sir, no swords were drawn, nor was there any killing. For two days the traders kept their shops closed. The magistrate toured the town and made them re-open their shops, using threats and persuasion. Goats were sacrificed, and a few cows too.

Letter to Saaduddin Khan Shafaq

The victim of the arrows of misfortune, Ghalib, conveys his respects to you. When I read your letter I realised I had made a blunder in striking off a phrase (in your verse) which was perfectly all right …. I do not know how I drew a line across it. I seem to have lost my senses and my memory is playing tricks. I write many words without intending to do so. After all I am 70, and how can I prevent nonsense from creeping into my writing? I own my sin in making the change in your verses and seek forgiveness.

Letter to Munshi Hargopal Tufta

The greater part of my life is over and only a little is left. I have lived well and will manage to live well what remains of my days. I ask you what did Urfi gain from the success of his quaseedas (panegyrics)? What shall I gain from getting my quaseedas known? Of no avail was the Bostaan of Saadi to him. Of what avail will your Sumbalistaan be to you? Everything outside Allah is insubstantial and fleeting. There is no poetry and no poet, no quaseedas and no plans for the future. Nothing exists except Allah.

No wonder his words still cast magic on us.