“Huge Chinese armies have been marching in the northern part of NEFA. We have had reverses at Walong, Se La and today Bomdila, a small town in NEFA, has also fallen. We shall not rest till the invader goes out of India or is pushed out. I want to make that clear to all of you, and, especially our countrymen in Assam, to whom our heart goes out at this moment.”

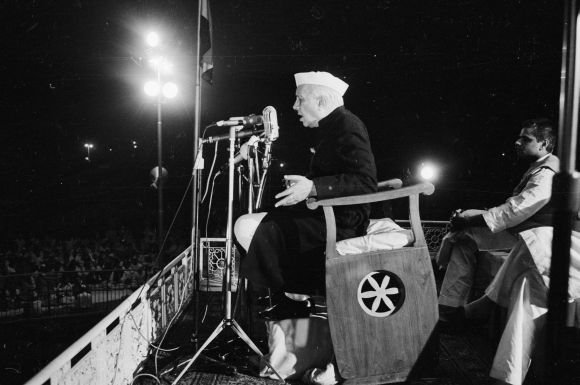

These words belonged to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as he addressed the nation on All India Radio on November 20th, 1962, while the Sino-India war was going on. A wave of panic swept across Tezpur, a town on the banks of the river Brahmaputra, as the Prime minister said “my heart goes out to the people of Assam”. Bomdila – about 150 km from Tezpur – had fallen to the Chinese and there was every possibility that the Chinese army was heading towards Tezpur.

This speech made people of Assam feel abandoned. It was like they were let down by their own government. At a time when even the Prime Minister seemed helpless, what was going to be their fate?

Historians claim that Nehru couldn’t assess the Chinese stand on the Indo-China international boundary. They insist that India should have realized their intention way back in 1956-57 when China began construction of the Aksai Chin road. As far as India is concerned, that had belonged to us.

Another issue was China’s Tibet occupation and India giving asylum to Dalai Lama, the Tibetian religious leader, along with 1,00,000 refugees, who took shelter in India. It was the town of Tezpur where Dalai Lama was given a warm welcome. Little did the residents knew what it was going to cost them in the future.

As India and China were moving towards war, the presence of the army grew in Tezpur. Even women were being trained by the Home Guard for civil defence duties. On October 20th, 1962, war had begun and there were rumours of Chinese occupation everywhere in Tezpur. People had already begun to leave their homes and then came this speech by the PM, extending his sympathies to the residents of Assam.

It was panic everywhere in Tezpur and people were leaving their homes by bus, car, cart, truck, cycle and even on foot. Back in the day, there was no bridge connecting the north and south banks of Brahmaputra so to get to Guwahati, people had to take a steamer. It was a chilly winter and families would wait for the ferry along the open ghats and set up campfires in the night.

Tea planters, most of whom were British or Scottish, packed their belongings, handed over the administration of their tea-plants to their Indian managers or staff, gave away their pets or shot them dead, and flew to Calcutta.

An eerie silence swept across the town with only a few people remaining, including the administration. As they were readying up to leave, the manager of the State Bank of India, Tezpur branch, piled up all the currency notes and burnt them down to prevent them from getting into Chinese hands. Because the coins couldn’t be burnt, they dumped them into Padam Pokhri, a nearby pond.

Nonetheless, at midnight on November 21, 1962, China declared ceasefire and there was no Chinese army in Tezpur. But the fear of foreign occupation was such that people continued to flee their homes even after a unilateral ceasefire. Some people believe that the mass exodus was a result of the wrong assessment of the situation by the central government.

It took quite some time for Tezpur to return to normal life, but listening to stories from people who witnessed the fear of Chinese aggression still gives us the chills.