Long ago, when mankind was still in its infancy, there existed a civilisation with well planned cities and advanced municipal sanitation, where trade was the main occupation of its people and where they were ahead of the rest of the planet by a large margin. The Harappan civilisation or the Indus Valley civilisation still remains a big question for historians, due to very little evidence remaining at excavation sites.

Since the city is so old, much of what they built was lost to the winds of time and a huge chunk of what is arguably, the most important civilization in our country in terms of technological advancement, was lost forever.

During various site excavations, archaeologists were left highly impressed with the intricately designed artifacts and the advanced and systemic management of the city.

But, one startling mystery is still left unanswered. How did this great civilisation come to an abrupt end? No one knows for sure. A lot of archaeologists have had many differing theories but none of them have come to a concrete conclusion.

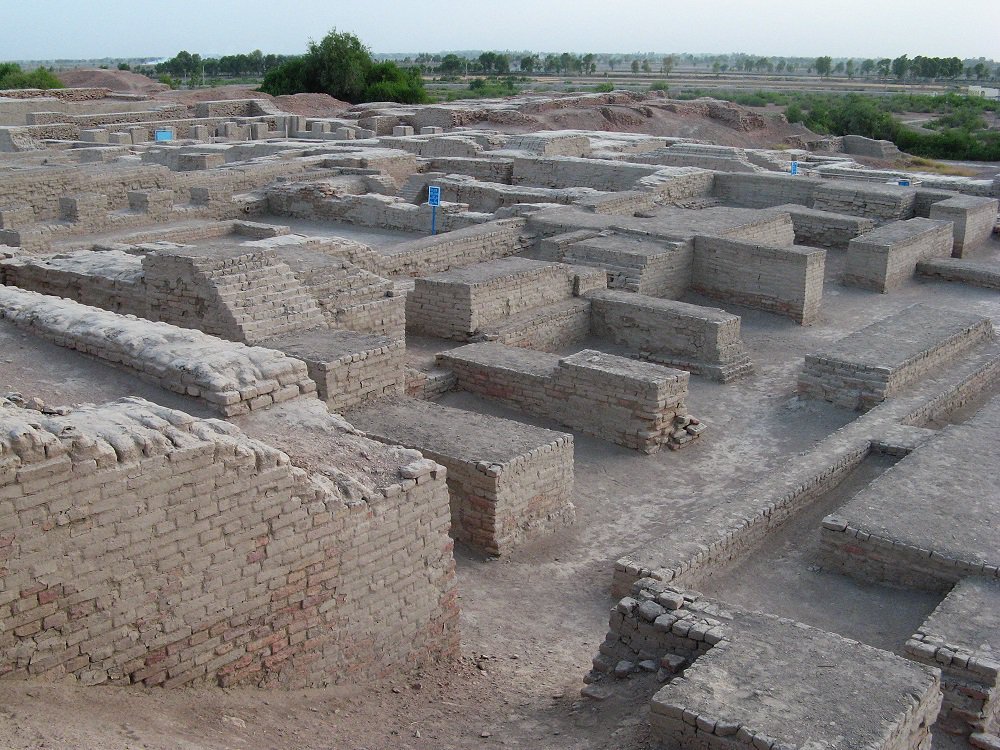

Regarded as one of the earliest human settlements in the world, the Indus Valley civilisation extended from present day northern Afghanistan to Pakistan and the north-western parts of India. Mohenjo-daro, the largest city of the Harappan civilisation lies on the west of the Indus river, in the Sindh province of Pakistan. Imagine a city around 4500 years old, with incredibly well-planned street grids and an elaborate drainage system. No doubt that the citizens of this ancient city were excellent urban planners.

Just a mental note, this is the correct way to spell ‘Mohenejo-daro’, not how the film decided to spell it.

Now, back to our scheduled programming.

Almost every house in Mohenjo-daro had a private bathing area with drains which rerouted dirty water out into a larger drain, which then emptied into a proper sewage drain to be disposed of.

Not too different from today’s sewage system, huh?

While Mohenjo-daro is a fairly new name given the city, (which actually means Mound of The Dead Men) its original name is still unknown. But, according to the interpretation of a prominent historian, Iravatham Mahadevan, its original name could have been Kukkutarma, as cock-fighting may have been a religiously significant activity in the city. In fact, chickens were reared not as food but as as sacred animals.

Unlike ancient India, where religion dominated every sphere of life, Mohenjo-daro does not show any evidence of religious governance or a monarchy, for that matter. Historians suggest that the city was perhaps governed as a city-state, by elected officials. A sort of old-school democracy, so to speak.

Surprisingly, the city did not have any huge palaces, temples, or monuments either. However, the artifacts discovered from the city are excellent in design and raw build that they’ve even stood the test of time.

Fired and mortared bricks were used to construct buildings in Mohenjo-daro, which also led to the building of superstructures. It was a wealthy city where the elite had much more land, larger houses and a better standard of living than the rest of the citizens. The city was divided into two main sections. The citadel and the city. The citadel was a mud-brick mound with a large public bath, a residential building with a capacity of 5000 people, and two large assembly halls. The city was a space where people gathered in large numbers and it had a central market place as its main attraction. Seals and weights from different regions around the world discovered in the excavation site also tell us that trade thrived in the city.

An underground furnace was found by archaeologists in one of the buildings. It was possibly used to heat public baths. There were many two-storeyed buildings in the city as well. This just goes to show that even without modern technology, the citizens of this ancient city were truly ahead of their time when it came to architectural prowess.

The people of Mohenjo-daro gave cleanliness and hygiene paramount importance, which is evident from the Great Bath, discovered in the city. Many archaeologists believe that the Great Hall would be a more appropriate name for a building as huge as it is.

There were two staircases which were used to enter the Great Bath. The bath also had a water-tight floor with finely fitted bricks laid on the edges, and was sealed up with the help of gypsum plaster.

A remnant of the incredibly well-planned drainage system can be seen in the Great Bath. Its floor tilts down towards the southwest corner, where a small outlet leads to a brick drain, which carries the water to the edge of the mound.

One of the most important discoveries found at the site, is a bronze statuette. It has been named the Dancing Girl by historians. It was the favourite item of the British archaeologist, Mortimer Wheeler. In a statement he made about the statue he said:

She’s about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There’s nothing like her, I think, in the world.

Another important artifact discovered from the site was a soapstone figure of a bearded man. Although, the city shows no sign of religious rule, archaeologists dubbed this figure, the Priest-King.

His hair is combed backwards and he has a neatly trimmed beard. There are two holes beneath his ears, which probably meant that he wore an ornament around his neck. Studies suggest that the Harappan people wore many ornaments on their body. This figurine still remains a mystery to this day.

With trade being the lifeline of this civilisation, many varied seals have been discovered at the site. Some belong to Mesopotamia, indicating that the Harappan people were engaged in trade with people from an ancient version of Iran. A seal discovered at the site had an image of a figure sitting cross-legged, surrounded by animals, which some scholars interpret to be a yogi or a three-headed proto-shiva.