One of the few crucial things the December 16 Delhi gang-rape did to the consciousness of Indians was to bring home the naked grim reality of rape culture and rampant misogyny seeped in society.

Not undermining the discourse shaping up after the incident in India, talking about rape became a focal point among governance and social setups, resulting in a number of changes in law and punishment to rapists.

Loud claims about safety of women do rounds each time there is an incident of rape. A string of mobile applications that promptly send alarms to law enforcement agencies and close ones, have become ubiquitous on almost every memory card. These allow the women to reach quickly for help in case they fear about their safety. But have these apps stopped rape?

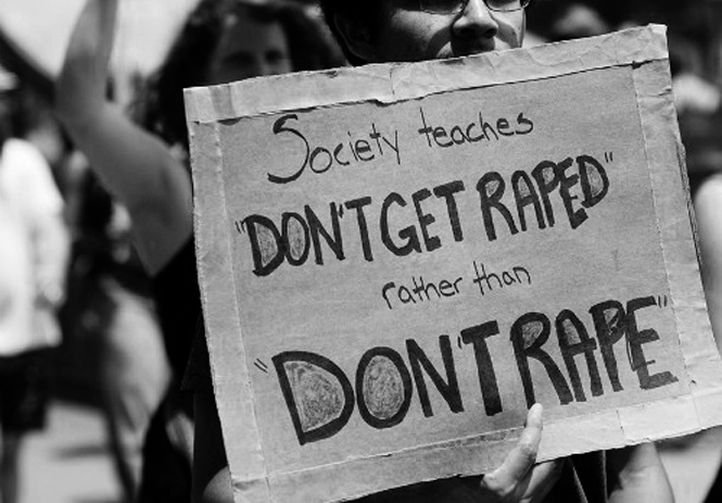

We assume you know the answer, pretty well. Tested and proposed ways to deal with rape — by advocating self-defence training, pepper sprays, GPS trackers, rape whistles and so on — might be helpful in repelling the rapist, but not the attitude which drives the act.

Cosmetic measures

As of now, thousands of mobile apps and cosmetic measures for ‘protection and safety’ of women are in markets not only in India but throughout the world. Undeniably, the apps might have helped a lot of women and still do, but the burgeoning of safety apps is obscuring the roots of the problem — rape culture.

Recently, a map-based mobile safety app ‘Safetipin’ was launched as part of a United Nations initiative to stem cases of rape, sexual harassment and molestation in urban areas. It acts as a personal GPS tracker, allowing users to be tracked or to trace a loved one. The app uses crowd sourcing to rate the safety of particular areas based on factors such as lighting, population density, transport and gender diversity.

Recognizing the initiative’s objectives, the app definitely provides a woman with tool of defence, albeit not of the level it should be. At the same time, the initiative, like almost all the apps, doesn’t address questions and situations of rape at home or someone known to the victim.

Statistics reveal an ugly reality

In 2012, out of 24,923 rape cases reported across India, 24,470 cases (ie 98 per cent) were committed by someone known to the victim, National Crime Records Bureau 2013 Annual report says.

One wonders over the usage, if any, of a mobile app in these cases. The quick answer might be: let’s customize the app to send alarm signals as soon as a woman fears an assault. But is that possible?

Do we expect women to keep their cell-phones tied to their bodies always? What kind of safety is this where a woman is always under a persistent fear to get raped, by anyone, anytime: colleague, bus/cab driver, father, brother, husband, brother-in-law, ‘upper-caste’ chieftain, ‘lower-caste’ minion, policeman, an army man and so on.

Ironically, attempts and efforts at bringing attitudinal transition and sensitization in the perceptions and frame of view, vis-a-vis women, exist only in the shadows.

Rape is a tool of power, for lack of a better phrase, rather than any ‘explained’ narrative of being fueled by sexual urges, short clothes or consuming certain varieties of food. Unfortunately, there’s no mobile app to deal with this kind of mental setup.

Also, when it comes to rape culture, the kind of response in recent years has had much to do with addressing the problem through economic-class hierarchy rather than through an egalitarian approach of treating victims of violence on the same plane.

Does it need any hard guesses to determine how many women use smartphones and how many can’t afford it. India is a developing nation, but among the poorest too. It’s more of an agriculture-run-rural majority country than a touted technological urban hub of metros and 4G.

While the number of reported rapes in Delhi rose from 1,636 in 2013 to 2,166 in 2014, this is only a tinge of reality about rape in the country. NCRB reports state that the number of reported rapes in India are only an estimated 1% of the total number of rapes that take place annually in the country.

A country where at least 636 million people lack toilets , advocating mobile apps and karate training to protect women from rape is beyond the borders of absurdity. Needless to say, it only saves, if at all, a particular group of women from sexual assault.

What about Dalit and other ‘lower-caste’ women? Hasn’t rape been normalized as a form of punishment by ‘upper-caste’ men on women and girls of other class in a number of Indian states over centuries of oppression?

A UN study of 57 countries estimates just 11% of rape and sexual assault cases worldwide are ever reported.

How many Dalit Nirbhayas do you remember?

The reality is that the kind of anti-rape attitude arising after Nirbhaya gang rape was a late acknowledgement of home truth, that had been around for decades but hardly noticed.

Rape as a tool of power

Even the government’s ‘selective’ agility towards some rape cases and ‘dead silence’ towards others, provide firm grounds for the assumption that state itself condones rape.

Take an example of rape by armed forces in conflict ridden areas like Kashmir or North-East. While all of India seemed to be on roads after December 16, a deafening silence looms when an army or BSF man rapes a woman in Kupwara or Kokrajhar.

How rapists think was well illustrated by the interviews of December 16 gang rape convict Mukesh Singh in the banned BBC documentary India’s Daughter . Mukesh’s statements might have come as a surprise to many, but this is how men, brought up in an atmosphere of patriarchy and remorselessly institutionalized misogyny believe. He is not alone.

There are many Mukeshs, roaming and prowling, everywhere and if you think an SOS button push is going to stop them, you’re wrong, even if you are saved at that time.

Rape is a reality. Not an android feature.